Maryland, a state rich in history and pivotal in the narrative of the United States, holds a unique origin story rooted in religious motivations and the quest for tolerance. Understanding “Why Was Maryland Founded” takes us back to 17th-century England and the aspirations of the Calvert family, particularly Cecil Calvert, the second Lord Baltimore.

To truly grasp the reasons behind Maryland’s founding, it’s crucial to understand the religious and political landscape of 17th-century England. The Virginia colonists, who had established Jamestown in 1607, found themselves apprehensive in 1634. Their unease stemmed from the impending arrival of English Roman Catholics as their northern neighbors. In an era where religion and politics were deeply intertwined, England had firmly embraced Protestantism since Queen Elizabeth I. However, King Charles I, in 1632, granted a charter to Cecil Calvert to establish a colony in the Chesapeake region, adjacent to Virginia. This was significant because Cecil and his father, George Calvert, had converted to Roman Catholicism in the 1620s.

This development sparked anxieties among the Virginians. Fears of religious conversion, challenges to the King’s authority, and potential alliances between English Catholics and Catholic powers like Spain and France loomed large. The prospect of a Catholic stronghold along the Atlantic coast was a significant concern for the predominantly Protestant colonies.

The Calverts were acutely aware of these apprehensions. Their vision for the colony was to create a sanctuary for English Catholics, who were facing persecution in their homeland. They feared that anti-Catholic sentiment could jeopardize the success of their colony, named Maryland in honor of Queen Henrietta Maria, King Charles’s wife. To allay Protestant fears, the Calverts published “Objections Answered Touching Maryland.” In this document, they sought to dispel the notion that they posed a threat to the Protestant colonies of Virginia and New England. They reassured their Protestant countrymen that there was no conspiracy to undermine the English Crown, align with Spain, or convert their Protestant neighbors. The Calverts emphasized that the Maryland colonists simply desired the freedom to practice their Catholic faith and coexist peacefully with those of different beliefs.

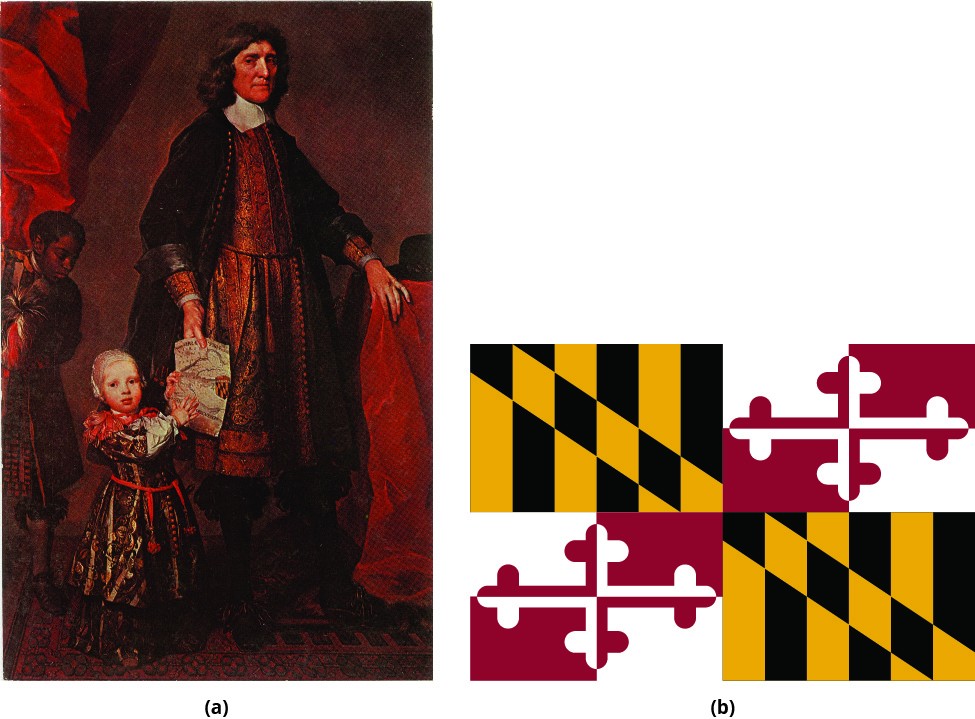

(a) Cecil Calvert, the second Lord Baltimore, envisioned Maryland as a haven where Catholics could freely practice their religion. This seventeenth-century Dutch portrait captures his likeness. (b) The Maryland state flag proudly displays the black and yellow Calvert coat of arms, also visible in the document held by Calvert in the portrait, representing the state’s founder and historical roots.

However, the reality of Maryland’s early demographics diverged from the Calverts’ initial vision. Contrary to their expectations, relatively few English Catholics made the transatlantic journey. Instead, the colony attracted a larger influx of Protestant dissenters, including Quakers and Puritans who disagreed with the Church of England. Maryland, intended as a Catholic colony, evolved into a religiously diverse society. The challenge then shifted to establishing harmony and order among this diverse population, composed of religious outsiders and members of the Church of England.

To address this challenge, in 1649, the Maryland Assembly took a groundbreaking step by proposing and passing the “Act Concerning Religion,” historically known as the Maryland Toleration Act. This landmark legislation aimed to prevent religious conflict within the colony. It prohibited Marylanders from using derogatory religious terms against one another, listing examples such as “heretic, schismatic, idolater – popish priest, Jesuited papist – or any other name or term in a reproachful manner relating to matters of religion.” More significantly, the act declared that all Christians were free to worship according to their conscience, provided they believed in the Holy Trinity and the divinity of Jesus Christ. This meant no Christian would face persecution for their faith, nor could they be compelled to attend services or pay tithes to another denomination.

The Toleration Act was truly revolutionary for its time. It marked the first instance in English law where freedom of religious exercise was promised to all Christians. Had this principle been fully embraced and consistently upheld, Maryland could have become the first place in the English-speaking world where Catholics, Protestants, and various Christian denominations could coexist peacefully.

Broadsides, large sheets of paper used for public announcements, disseminated information widely. This broadside, circulated in 1649, publicized Maryland’s Toleration Act, a decree ensuring that no Christian would be persecuted for their religious beliefs.

Unfortunately, the promise of religious harmony in Maryland was frequently disrupted by events unfolding in England. King Charles I’s own Catholic sympathies and his assertive exercise of monarchical power led to the English Civil War (1642-1645). Following Charles’s defeat and execution for treason in 1649, Puritan leader Oliver Cromwell rose to power in England. Under the authority of the English Parliament, Puritans seized control of Maryland. These staunch Reformed Protestants held no sympathy for Catholicism. They promptly repealed the Toleration Act and prohibited Catholics from openly practicing their faith.

The restoration of the English monarchy in 1660, with Charles I’s son, King Charles II, ascending to the throne, led to the reinstatement of the Toleration Act. However, tensions between pro-Catholic and Reformed Protestant factions in England persisted. Upon Charles II’s death in 1685, his brother James II, a Catholic, became king. Britain’s Protestants, increasingly wary of James’s affinity for France and Catholicism, reached a breaking point. In the Glorious Revolution of 1688, England ousted James II and installed the Dutch Protestant William of Orange, married to Mary, James’s daughter, as the new monarch. This revolution solidified the Protestant identity of the English monarchy. It also unleashed pent-up anti-Catholic sentiments in both England and its North American colonies.

Religion and politics formed a volatile mix in England and its colonies during the mid-to-late seventeenth century. The English Civil War culminated in the execution of Charles I, perceived as pro-Catholic, outside Whitehall Palace in London. Religious tensions persisted throughout the rule of Puritan leader Oliver Cromwell, Charles II (son of Charles I), and James II (Charles II’s Catholic brother), until the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

In Maryland, resentment towards the Catholic leadership had been simmering for decades. Despite Protestants constituting the majority of the population, Catholics maintained control of the proprietary government and had reinstated the Toleration Act. Many Protestants felt that Maryland’s religious liberty was a sham, arguing that Catholics disproportionately held power and wealth. Complaints arose about Catholic officials dominating political offices, imposing unfair taxes, and living lavishly while Protestant ministers struggled financially. Rumors even circulated among some non-Catholics alleging a Catholic alliance with the Seneca Indians aimed at “total destroying of all the Protestants.”

News of James II’s overthrow in England ignited celebrations among Maryland Protestants, while Catholics still hoped for James II’s return to power. Fueled by anti-Catholic sentiment, Maryland Protestants, led by Anglican minister John Coode, launched a rebellion against the Catholic proprietors. Coode’s Rebellion, an armed uprising, targeted the colonial capital, present-day Annapolis. When the Catholic government attempted to rally support to suppress the rebellion, they found little willingness among Marylanders. Ultimately, Lord Baltimore’s forces were compelled to surrender on August 1, 1689.

With a new Protestant governor installed, Maryland enacted a series of repressive anti-Catholic measures. The Toleration Act was once again revoked, Catholic worship was outlawed, and Catholics were disenfranchised, losing their right to vote. The groundbreaking religious freedom that Maryland’s Catholics had extended to Protestants in 1649 was not restored until the era of the American Revolution. However, the principle of religious liberty initially championed by Maryland in the Toleration Act, though initially limited to Christians, eventually expanded to encompass non-Christians and became a fundamental tenet of U.S. law, shaping the nation’s commitment to religious freedom.