Honey is often touted as a natural sweetener and a healthy food for adults and older children. However, when it comes to babies under one year old, honey can be dangerous. This article explores the reasons behind this warning, focusing on the risk of infant botulism associated with honey consumption in babies.

Infant botulism is a rare but serious form of food poisoning that affects babies under 12 months of age. It is caused by spores of the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. These spores are commonly found in soil and dust, and unfortunately, they can also be present in honey. While these spores are harmless to older children and adults because their mature digestive systems can handle them, a baby’s immature gut is a different story.

When a baby ingests Clostridium botulinum spores, they can germinate and multiply in the intestines. These bacteria then produce botulinum toxin, a potent neurotoxin. This toxin attacks the body’s nerves, leading to muscle weakness and paralysis.

The symptoms of infant botulism can vary in severity, but they often start with constipation. This is frequently followed by other signs, including:

- Lethargy and weakness: The baby may appear unusually tired, floppy, and less responsive. This “floppy baby syndrome” is a key indicator.

- Poor feeding: Difficulty sucking or swallowing, weak cry, and reduced appetite.

- Ptosis (drooping eyelids): Facial weakness can cause the eyelids to droop.

- Loss of head control: Difficulty holding the head up.

- Reduced reflexes: Decreased deep tendon reflexes.

In severe cases, infant botulism can lead to respiratory failure and even death. It is crucial to seek immediate medical attention if your baby exhibits these symptoms, especially if they are under one year old and have consumed honey.

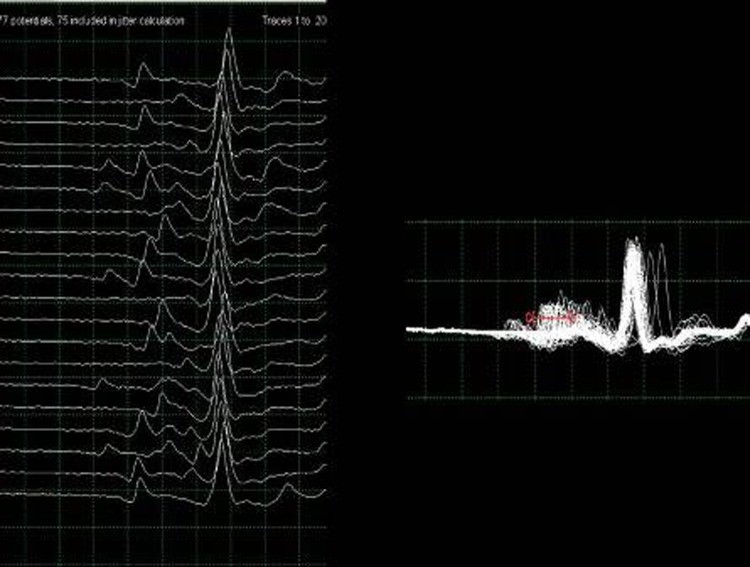

Figure 1: Electromyography results showing abnormality indicative of neuromuscular junction disorder in an infant botulism case.

To illustrate the danger, consider a case of a 3-month-old baby girl who presented with floppiness and other concerning symptoms. Initially, she showed poor feeding, constipation, and a cough. Upon examination, doctors noted generalized hypotonia, decreased reflexes, facial weakness, and poor head control. Extensive investigations were conducted to determine the cause of her condition.

Electromyography studies, as shown in Figure 1, revealed severe abnormalities consistent with a neuromuscular junction disorder. Further testing confirmed the presence of Clostridium botulinum type A neurotoxin in her stool, directly linking her condition to botulism toxicity. The source was traced back to honey she had ingested. Samples from the honey bottle fed to the infant also contained Clostridium botulinum type A spores, matching the strain found in the baby.

This case highlights the direct link between honey and infant botulism. While Clostridium botulinum spores are widespread in the environment, honey is a known dietary reservoir, making it a significant risk factor for babies.

Fortunately, this baby was treated with botulinum immunoglobulin and made a full recovery. This underscores the importance of prompt diagnosis and treatment. However, prevention is always better than cure.

The recommendation from health organizations worldwide is clear: do not give honey to babies under one year old. This includes all forms of honey, whether raw, pasteurized, or processed. It’s also important to be aware that honey is sometimes used in traditional remedies or as a prelacteal feed in some cultures. Education and awareness are key to changing these practices and protecting infants from botulism.

Infant botulism is a serious condition, but it is also preventable. By understanding the risks associated with honey and adhering to the guidelines of not feeding honey to babies under one year, parents can significantly reduce the risk of their child developing this illness. If you are concerned about infant botulism or have questions about feeding your baby, always consult with your pediatrician or a healthcare professional.

References (based on original article, may need adaptation for a general audience):

- Midura TF, Arnon SS. Infant botulism. Lancet. 1976 Jul 17;2(7976):93-4.

- Pickett J, Berg B, Chaplain E, et al. Syndrome of botulism in infancy. Clinical and electrophysiologic study. N Engl J Med. 1976 Dec 9;295(15):770-3.

- Schechter R, Veysey M, Mittelman M, et al. Infant botulism in Africa: first confirmed case. S Afr Med J. 2007 Aug;97(8):589-90.

- নেওয়া হয়, et al. Infant botulism in the United Kingdom. Euro Surveill. 2007 Nov;12(11):E070117.1.

- নেওয়া হয়, et al. Clinical spectrum of infant botulism: a 20-year review. J Pediatr. 1998 Nov;133(5):616-23.

- Tanzi MG, Gabay MP. Association Between Honey Consumption and Infant Botulism. Pharmacotherapy. 2002 Nov;22(11):1479-83.

- Arnon SS. Infant botulism. In: Feigin RD, Cherry JD, Demmler-Harrison GJ, Kaplan SL, eds. Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009:1685-94.

- Shapiro RL, Hatheway CL, Swerdlow DL. Botulism in the United States: a clinical and epidemiologic review. Ann Intern Med. 1998 Oct 15;129(6):480-6.

- صديقي, et al. Prelacteal feeding practices in Pakistan: reasons and implications for infant and child health. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2009 Dec;19(12):775-8.

- Agarwal KN, et al. Early feeding practices of neonates in India. Indian J Pediatr. 2006 Jun;73(6):489-93.