Boston, a city steeped in history and brimming with modern innovation, carries a curious nickname: Beantown. But Why Is Boston Called Beantown? For many, especially those outside of New England, the moniker might seem puzzling, even outdated. Is it a term of endearment, a historical relic, or simply a misnomer in today’s bustling metropolis? Let’s delve into the flavorful past of this nickname and explore why some argue it’s time to retire “Beantown” for good.

Illustration of a baked bean pot with Boston skyline in the background

Illustration of a baked bean pot with Boston skyline in the background

The nickname “Beantown” isn’t just a random label; it’s deeply rooted in Boston’s culinary and cultural history. However, as Boston evolves into a global hub of technology, education, and medicine, the question arises: does “Beantown” still accurately represent the city? For many residents and even tourists, the answer is increasingly no. Anecdotal evidence suggests the nickname is fading from everyday conversation. Imagine asking a local for directions in “Beantown” – you might be met with a confused look. Even visitors, the supposed target audience for such nicknames, often draw a blank when confronted with “Beantown.”

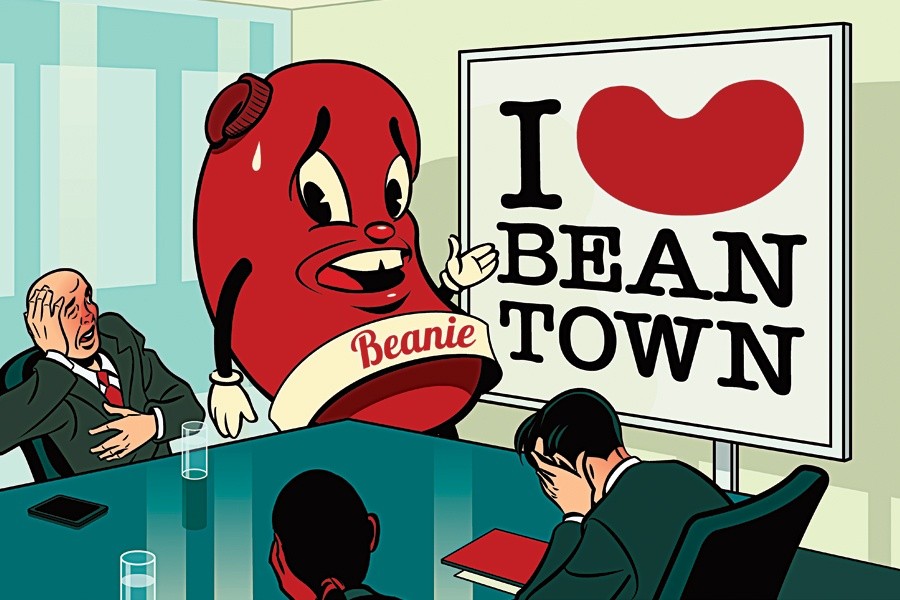

Take, for instance, the experience of Rhona Bergin, a tourist from Ireland. As recounted in Boston Magazine, she was taken aback when a relative commented “I love Beantown!” on her Boston Instagram post. Her reaction, “What’s ‘Beantown’?”, is far from unique. Adding to the confusion, her partner, Colm Byrne, even associated the “Bean” nickname with Chicago, home to the iconic “Cloud Gate” sculpture, affectionately known as “The Bean.” This highlights a critical point: in the public consciousness, if “Beantown” resonates at all, it’s increasingly vague and easily misattributed.

Further diminishing the nickname’s relevance is the sheer difficulty in finding authentic Boston baked beans in Boston itself. Jim Healy, a veteran of Boston Duck Tours, recalls only one instance in nearly three decades of a tourist specifically asking for Boston baked beans, whom he directed to the now-closed Durgin-Park. The irony is palpable: a city nicknamed “Beantown” where its namesake dish is becoming a culinary ghost. The potential transformation of the historic Durgin-Park location into a cannabis dispensary further underscores this shift away from Boston’s traditional culinary identity.

This brings us to a crucial juncture. Boston is burdened with a nickname that feels increasingly out of sync with its contemporary identity. It’s a moniker that is largely unfamiliar to its own residents, perplexing to many tourists, and linked to a dish that’s becoming increasingly elusive within city limits. It begs the question: should a city renowned as the cradle of the American Revolution, a global leader in higher education, and a powerhouse of medical and technological innovation be primarily known for a legume dish, however historically significant? Many argue that clinging to “Beantown” is not only outdated but also diminishes Boston’s multifaceted and dynamic character.

We’re a town with a moniker that is meaningless to most residents, unknown to many tourists, and refers to a dish that is increasingly tough to find.

To fully appreciate the debate around “Beantown,” understanding its origins is essential. Baked beans, in fact, predate European colonization of the region. Native Americans were the original creators of this dish, using maple syrup and bear lard. When European settlers arrived, they adapted the recipe, incorporating ingredients like pork, brown sugar, and molasses. Molasses, in particular, held a significant place in early American history. John Adams famously called it “an essential ingredient in American independence” due to its exemption from British taxes – a detail often conveniently overlooking molasses’s dark connection to the slave trade. The association of Boston with baked beans solidified further with the Puritan tradition. Observing a strict Sabbath, they would prepare large pots of baked beans on Saturdays to sustain them through Sunday without cooking. This weekend ritual led visitors to identify Boston as “Beantown.”

However, the popularization of “Beantown” as a widespread nickname is largely attributed to a shrewd political move in the early 20th century. Mayor John F. Fitzgerald, affectionately known as “Honey Fitz” and grandfather of President John F. Kennedy, spearheaded a campaign to promote Boston using baked beans. Inspired by New Hampshire’s “Old Home Week,” aimed at attracting tourists and former residents, Fitzgerald launched a similar initiative in Boston in 1907. He envisioned it as “a splendid opportunity to stimulate public sentiment here and to advertise to the world the progress that Boston has been making.”

As part of this campaign, the city distributed a million stickers nationwide, all emblazoned with a baked bean pot. The highlight of “Old Home Week” was declared “Boston Baked Bean” day, officially cementing “Beantown” in the city’s promotional vocabulary. This strategic marketing effort, rather than organic popular adoption, played a crucial role in establishing and perpetuating the “Beantown” nickname.

The “Beantown” moniker further permeated popular culture throughout the 20th century. Boston’s National League baseball team was even named the Beaneaters, and postcards boasted slogans like “You Don’t Know Beans Until You Come to Boston.” The enduringly popular Beanpot college hockey tournament, established in the 1950s, further ingrained the nickname in local consciousness. Even in the 1980s, CBS aired a sitcom titled Goodnight Beantown, though it had a short run. Despite these cultural touchpoints, the tangible connection to baked beans themselves has waned. While Union Oyster House remains one of the few restaurants still serving the dish, as their Executive Chef Rico DiFronzo notes, it’s often seen as a historical novelty alongside other classic New England fare like fish chowder. He draws a parallel to Philadelphia and cheesesteaks, but points out a key difference: Philadelphia isn’t called “Cheesesteak-town.”

Looking at cities that have successfully rebranded themselves offers valuable lessons for Boston. Las Vegas provides a compelling example of the power of a well-crafted slogan. The “What Happens Here, Stays Here” campaign, launched in 2003, dramatically reshaped Las Vegas’s image and boosted its cultural and economic appeal. This multi-million dollar campaign exemplifies the investment and strategic thinking required for effective city branding. It underscores that a successful slogan can significantly impact a city’s trajectory.

Conversely, the pitfalls of rebranding are equally important to consider. Rhode Island’s disastrous “Cooler & Warmer” campaign in 2016 serves as a cautionary tale. The nonsensical slogan, coupled with a commercial featuring footage from Iceland, was met with widespread ridicule and ultimately led to the campaign’s cancellation and the marketing official’s dismissal. This example highlights the risks of poorly conceived and executed rebranding efforts, emphasizing the need for careful research, public consultation, and genuine reflection of a city’s identity.

For Boston, the path forward involves a thoughtful and strategic approach to its city branding. Moving beyond “Beantown” doesn’t necessitate erasing history but rather evolving with the times and embracing a more comprehensive representation of Boston’s current strengths and aspirations. The Greater Boston Convention & Visitors Bureau faces the challenge of crafting a new slogan that captures the essence of modern Boston – its innovation, its intellectual dynamism, its historical significance, and its vibrant culture. This requires a commitment to investing time, resources, and creative energy to discover and articulate what truly makes Boston exceptional in the 21st century. A successful rebranding effort could be transformative, solidifying Boston’s image as a forward-thinking global city while respectfully acknowledging its rich heritage. It’s time to consider whether saying “Goodbye to Beantown” is a necessary step towards a more accurate and compelling representation of Boston to the world.