Have you ever paused to consider why ice cubes bob merrily on the surface of your drink instead of sinking to the bottom? It seems like a simple observation, yet the reason behind it delves into fascinating physics and the unique properties of water. Let’s explore the science behind why ice floats on water.

The Physics of Floating: Density and Buoyancy

The secret to floating lies in density. An object will float on water if it is less dense than water. This principle is explained by Archimedes’ principle, a cornerstone of fluid mechanics.

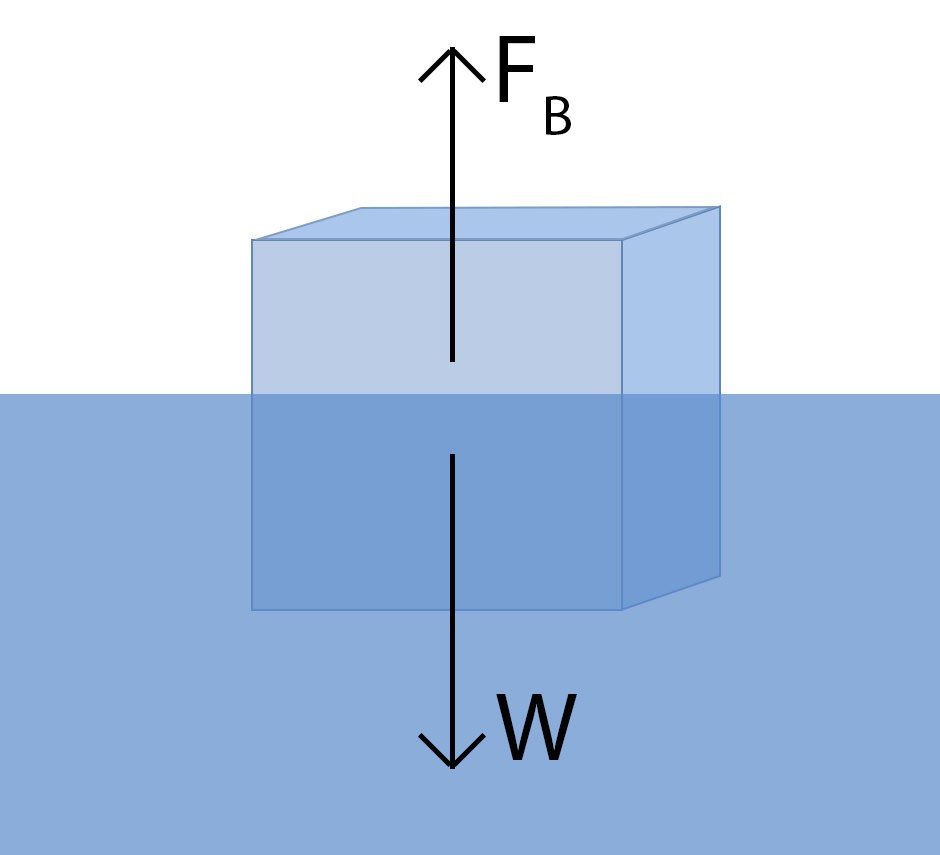

Imagine placing an object into a glass of water. You’ll notice the water level rises – the object displaces some water. Archimedes’ principle states that the buoyant force pushing upwards on the object is equal to the weight of the water displaced by the object. This upward force, known as buoyant force (FB), counteracts gravity.

Mathematically, we can express this. Weight is mass times the acceleration due to gravity (g). Density is mass divided by volume, so mass equals density times volume. Thus, the buoyant force (FB) can be expressed as:

FB = density of water × volume of displaced water × g

For an object to float, the buoyant force must be equal to or greater than the object’s weight. Archimedes famously realized that the volume of displaced water is equal to the volume of the submerged portion of the object.

Therefore, the buoyant force becomes:

FB = density of water × volume of submerged object × g

The weight of the object (W), acting downwards due to gravity, is:

W = density of object × volume of object × g

For floating to occur (FB ≥ W), density of water × volume of submerged object × g ≥ density of object × volume of object × g. Since ‘g’ and ‘volume of submerged object’ (which is equal to the volume of the object if fully submerged, or less if partially submerged) are present on both sides, the crucial factor becomes density. An object floats if its density is less than the density of water.

Essentially, if an object is less dense than water, the upward buoyant force will overcome the downward force of gravity, causing it to float.

Why Solids Are Usually Denser Than Liquids

Typically, for most materials, the solid state is denser than the liquid state. Materials exist in different states of matter – solid, liquid, and gas – depending on how their particles are arranged.

In a solid, molecules are tightly packed in an ordered structure called a crystal lattice. This arrangement maximizes the number of molecules in a given volume, resulting in higher density.

When heat is applied to a solid, molecules gain energy and vibrate more vigorously. Eventually, they gain enough energy to break free from the rigid lattice structure, transitioning into a liquid state. In a liquid, molecules are still close together but have more freedom to move around.

As a substance transitions from solid to liquid and then to gas, the particles generally spread out further, leading to a decrease in density.

Water: An Exception to the Rule

Water, however, is an exception to this common rule. Ice, the solid form of water, is less dense than liquid water, which is why ice floats. This unusual property is due to hydrogen bonding.

A water molecule (H₂O) consists of one oxygen atom and two hydrogen atoms in a V-shape. Oxygen is more electronegative than hydrogen, meaning it attracts electrons more strongly. This unequal sharing of electrons creates a slight negative charge near the oxygen atom and slight positive charges near the hydrogen atoms.

These partial charges on water molecules lead to intermolecular attractions called hydrogen bonds (though not true bonds in the chemical sense). In liquid water, hydrogen bonds constantly form and break as molecules move, allowing them to be close together.

When water cools and begins to freeze, hydrogen bonds become more stable and ordered. The molecules arrange themselves into a crystal lattice structure, but the hydrogen bonds force a specific geometry that actually spaces the molecules slightly further apart than in liquid water. This expanded structure of ice means that for the same mass, ice occupies a larger volume than liquid water, making it less dense.

The Expansion of Ice and Its Powerful Force

Water reaches its maximum density at around 4°C. As it cools further towards freezing, it begins to expand. Upon freezing into ice, its volume increases by approximately 9%. This expansion is not just a curious phenomenon; it exerts tremendous pressure.

Ice has a bulk modulus of about 8.8 x 10⁹ Pascals. If you completely fill and seal a rigid container with water and freeze it, the pressure inside can reach approximately 790 megapascals (or 114,000 pounds per square inch!). This immense pressure, as noted by Professor Martin Chaplin, a leading expert on water’s properties, is beyond the capacity of any known material to withstand without breaking.

Freezing Water Under Pressure

What if water is confined and prevented from expanding when freezing? As water cools under confinement, pressure builds rapidly as more molecules transition to the ice lattice structure. If the container remains intact, at around 200 megapascals (roughly 2000 atmospheres), the water molecules will rearrange into a denser ice form.

In fact, there are at least 13 known forms of ice, stable under different temperature and pressure conditions. Ordinary ice is known as ice Ih. Under high pressure, denser forms like ice III can form. In a closed container, freezing water under pressure can result in a mixture of ice Ih and denser ice forms like ice III, as the system reaches an equilibrium. As explained by Keiron Allen, understanding these different ice phases reveals the complex behavior of water under extreme conditions.

In conclusion, the reason ice floats on water boils down to density. While most solids are denser than their liquid counterparts, water’s unique hydrogen bonding causes ice to be less dense, leading to the familiar sight of ice cubes floating in our drinks and having profound effects on aquatic environments and climates across the globe.