In Octavia Butler’s seminal novel Kindred, Dana Franklin, a contemporary Black woman, is repeatedly and inexplicably transported from her 1970s California home to pre-Civil War Maryland. While Damian Duffy and John Jennings’ graphic novel adaptation of Kindred vividly captures the emotional depth of Butler’s narrative, as explored in previous analyses of its visual storytelling, a crucial question persists: why does Dana run away in Kindred? While literacy and knowledge are recurring themes, the act of running away is a pivotal moment driven by a complex interplay of factors beyond the limitations of literacy in a slave society.

The original blog post on interminablerambling.com insightfully analyzes the role of literacy in Kindred, arguing that while Dana and her husband Kevin possess advanced literacy, it fails to liberate them from the brutal realities of Antebellum Maryland. Drawing parallels to historical figures like Frederick Douglass and Solomon Northup, the post highlights how literacy, often seen as a pathway to freedom in African American narratives, does not guarantee escape from subjugation in Kindred. However, to fully understand why Dana runs away, we must delve deeper into the specific circumstances that compel her to this desperate act, even within the context of her literacy and broader struggle for agency.

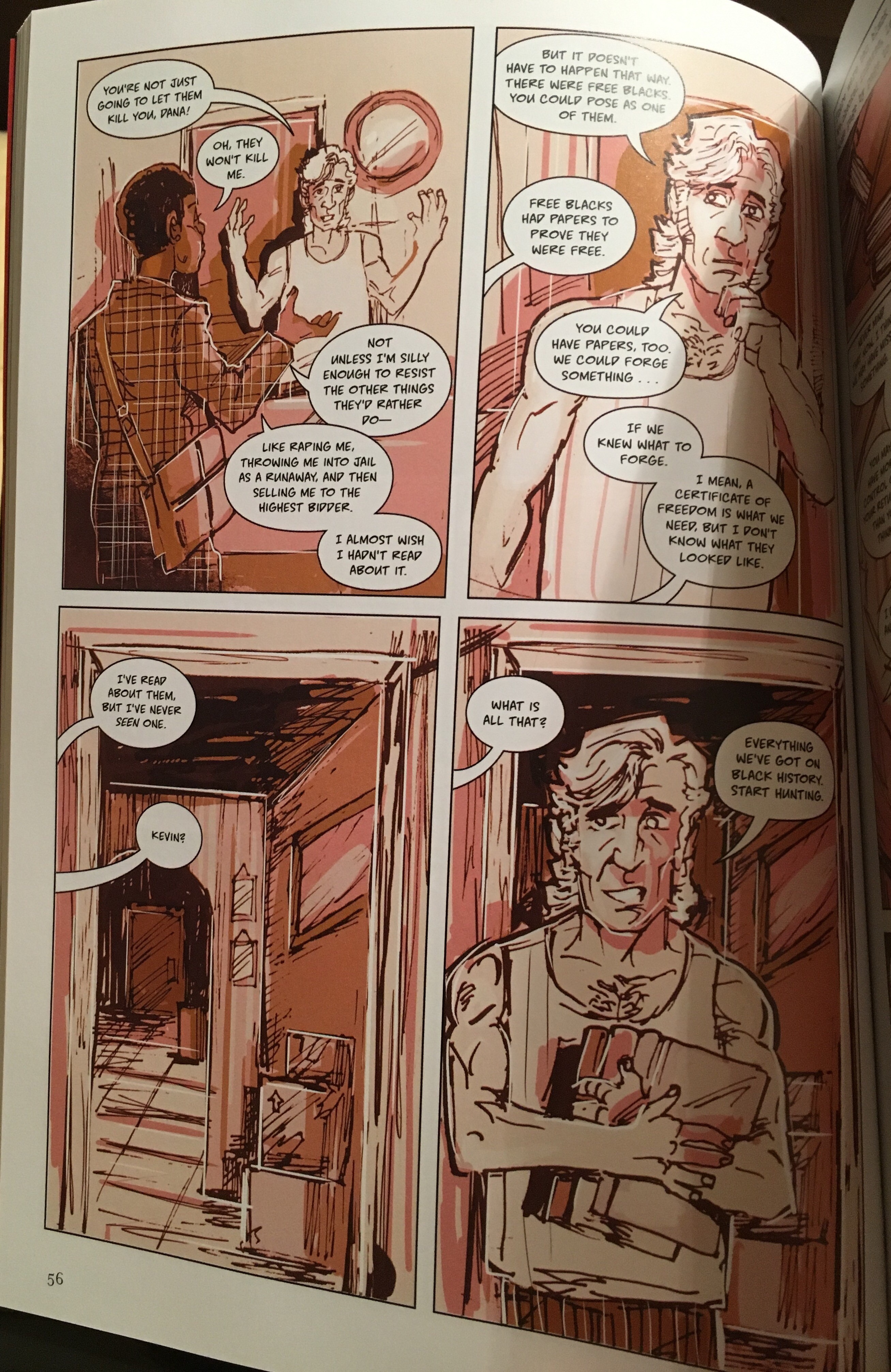

As the original analysis points out, literacy is presented as an insufficient tool for liberation in Kindred. Figures like David Walker and Frederick Douglass championed literacy as a means to empowerment and escape from slavery. Douglass himself recounts how learning to read and write facilitated his own path to freedom. However, Kindred presents a starkly contrasting reality. Solomon Northup’s narrative, while ghostwritten, also underscores that literacy alone could not prevent his kidnapping and enslavement. Similarly, Dana and Kevin’s literary prowess as writers is rendered impotent against the systemic oppression of the past. Their knowledge of history and even the concept of “free papers” proves useless when they lack practical examples to forge them, highlighting the disconnect between intellectual understanding and survival in a slave society.

Dana’s experiences on the Weylin plantation further illustrate this point. Despite her attempts to impart literacy to Rufus and Nigel, these efforts do not alter the power dynamics or offer a direct path to escape for anyone. Nigel’s quick learning does not translate into immediate freedom, and Rufus, despite his resistance to literacy, maintains his position of power as a white slave owner. Tom Weylin’s brutal whipping of Dana for teaching enslaved people to read reinforces the oppressive regime where literacy is not only discouraged but actively suppressed. Even Dana’s extensive reading about slavery in her own time, including works like Gone with the Wind, fails to equip her with practical solutions or protection when she is transported back.

The pivotal moment that directly precipitates Dana’s decision to run away is rooted in Rufus Weylin’s profound betrayal regarding her letters to Kevin. As the original analysis describes, Dana writes multiple letters to Kevin, who is stranded in the future, relying on Rufus to mail them. Rufus initially promises to do so but repeatedly withholds them. This act of deception is not merely about delaying communication; it is a deliberate exercise of power and control over Dana. Rufus’s manipulation keeps Dana isolated and dependent on him, reinforcing her enslaved status even as she performs labor that is atypical for enslaved people.

The revelation of Rufus’s treachery comes when Alice, another enslaved woman, shows Dana a collection of undelivered letters and envelopes. This discovery is a breaking point for Dana. It is not simply the delayed communication with Kevin that drives her to run, but the profound sense of betrayal and the realization that Rufus, despite moments of seeming connection or reliance on Dana, ultimately views her as property to be controlled and manipulated. The undelivered letters symbolize the false hope and broken promises that characterize Dana’s interactions with Rufus and, by extension, her precarious existence in the past.

Dana’s decision to run away is therefore not solely a reaction to the oppressive conditions of slavery in general, but a direct response to Rufus’s personal betrayal and the complete erosion of trust. It is an act of desperation born from the understanding that her literacy, her knowledge, and even her attempts at building a semblance of a relationship with Rufus have not fundamentally altered her vulnerability. Running away becomes the only remaining avenue for asserting agency, however risky and uncertain the outcome.

As the original analysis concludes, Dana’s ultimate escape is not achieved through literacy but through physical action – the violent act of self-defense that severs her arm and pulls her back to her own time. This physical resistance, born from a moment of intense struggle, highlights the limitations of intellectual or literary tools in the face of brutal physical oppression. Tom Weylin’s cruel remark, “Educated nigger don’t mean smart nigger, do it,” underscores the devaluation of Dana’s literacy in the eyes of the slaveholders and the primacy of physical control and dominance.

In conclusion, Dana runs away in Kindred not because of a sudden realization about the systemic injustice of slavery alone, but as a direct consequence of Rufus Weylin’s personal betrayal and manipulation. While the novel explores the theme of literacy and its limitations in achieving freedom, the immediate catalyst for Dana’s escape attempt is the loss of trust and the desperate need to reclaim some semblance of control over her life. Running away, though fraught with danger, becomes Dana’s ultimate assertion of agency in a world designed to strip her of it, highlighting the complex and deeply personal motivations behind acts of resistance in the face of enslavement.