Blinking is such a routine action that we rarely give it a second thought. It’s just something we do, like breathing or walking. However, this seemingly simple act of closing and opening our eyelids occupies a significant portion of our waking hours. In fact, humans spend approximately 3 to 8 percent of their time awake with their eyes closed due to blinking. This is quite a considerable amount of time to be visually disconnected from the world, especially when we consider that we blink more often than needed just to lubricate our eyes.

But if blinking momentarily obstructs our vision, why do we do it so frequently? Scientists at the University of Rochester have delved into this intriguing question and discovered that blinking serves a far more critical function than mere eye lubrication. Their research reveals that blinking plays an essential role in how our brains process visual information, challenging traditional understandings of vision itself. These groundbreaking findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The Unexpected Importance of Blinking in Visual Perception

Professor Michele Rucci, a faculty member in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at the University of Rochester, explains the core of their discovery: “By modulating the visual input to the retina, blinks effectively reformat visual information, yielding luminance signals that differ drastically from those normally experienced when we look at a point in the scene.” In essence, blinking is not a visual interruption but rather an active process that reshapes the visual signals our brain receives, contributing significantly to our perception of the world.

Decoding Vision in the Blink of an Eye

To unravel the mystery of blinking, Rucci and his team employed a combination of techniques. They meticulously tracked eye movements in human participants and integrated this data with sophisticated computer models and spectral analysis. Spectral analysis is a method used to examine the different frequencies within visual stimuli. This comprehensive approach allowed them to meticulously analyze how blinking alters visual input compared to when our eyes are continuously open.

Their experiments involved measuring human sensitivity to various visual stimuli, including patterns with different levels of detail. The results were surprising: blinking enhances our ability to detect large, gradually changing patterns in our surroundings. This indicates that blinking provides the brain with crucial information about the overall “big picture” of a visual scene.

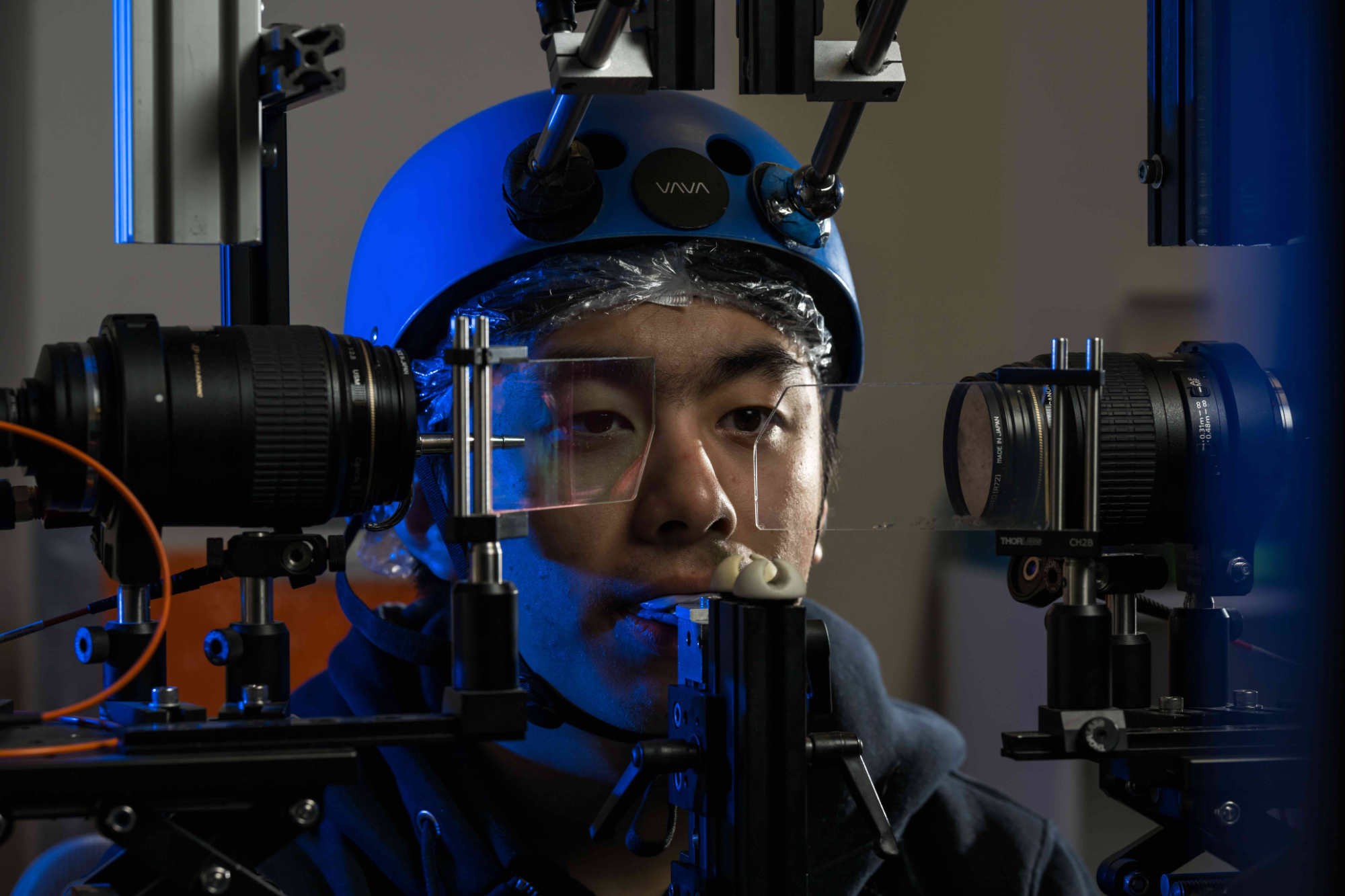

EYE MOVEMENT TRACKING: Owen Tu ’25 demonstrates the eye-tracking equipment utilized in Michele Rucci’s lab at the University of Rochester to explore the significance of blinking for visual processing. (University of Rochester photo / J. Adam Fenster)

“Contrary to common assumption, blinks improve—rather than disrupt—visual processing,” states the research team. The rapid movement of the eyelids during a blink modifies the light patterns that effectively stimulate the retina. This generates a distinct visual signal for the brain, unlike the signals received when our eyes are open and focused on a specific point. This altered signal appears to be beneficial for processing certain types of visual information.

BLINKS AND SPATIAL FREQUENCY: Research indicates that blinking emphasizes low spatial frequency – the overarching structure of a scene – playing a vital role in the brain’s visual information processing. The image illustrates the effect of spatial frequency on visual information. (Image provided by the Rucci Lab)

Bin Yang, a graduate student in Rucci’s lab and the lead author of the study, elaborates on this point: “Neurons respond strongly to temporal changes in their input signals and tend to not respond to unchanging stimuli. With their abrupt transients, blinks make the visual system respond strongly to the image on the retina. Thus, contrary to common assumption, blinks improve—rather than disrupt—visual processing, amply compensating for the loss in stimulus exposure.” In simpler terms, the brief interruption of vision caused by a blink actually makes our visual system more responsive and efficient in processing the incoming visual information.

Blinking and the Broader Understanding of Vision

These findings contribute to a growing body of research from Rucci’s lab that emphasizes the active nature of vision. Traditionally, vision was considered a passive process of simply receiving and interpreting images projected onto the retina. However, Rucci’s work suggests that vision, much like our senses of smell and touch, is deeply intertwined with motor activity. When we explore our environment through touch or smell, our body movements are crucial for the brain to understand spatial relationships. Rucci’s research strengthens the idea that vision operates in a similar manner, being far more dynamic and active than previously thought.

RETHINKING VISION: Professor Michele Rucci argues that “Vision resembles other sensory modalities more than commonly assumed,” highlighting the active role of blinking and eye movements in visual perception. (University of Rochester photo / J. Adam Fenster)

“Since spatial information is explicit in the image on the retina, visual perception was believed to differ [from other senses],” Rucci notes. “Our results suggest that this view is incomplete and that vision resembles other sensory modalities more than commonly assumed.” Therefore, blinking is not just a quirk of our biology but an integral part of our visual system, actively shaping and enhancing how we perceive the world around us. It’s a testament to the complexity and efficiency of the human brain, finding ingenious ways to optimize even the most commonplace actions like blinking for sophisticated sensory processing.