Flat GDP Growth Throughout History Indicating Poverty as Default State

Flat GDP Growth Throughout History Indicating Poverty as Default State

Being well-informed is often associated with the ability to explain complex issues. However, a more fundamental aspect is recognizing what truly needs explanation in the first place. What questions are genuinely intriguing and push us beyond superficial understandings?

In a recent interview with British politician Bridget Phillipson, interviewer Rory Stewart highlighted this point. Frustrated by her generic responses, he asked if she could recall an “intriguing” question that had allowed her to reveal a different perspective. Phillipson, seemingly taken aback, mentioned that children often pose the most challenging and insightful questions during her school visits. One example she cited was the profound question: “Why is there poverty in the world?”

Why Do People Ask “Why is There Poverty?”

It’s understandable why a child might ask “Why is there poverty in the world?”. It seems like a weighty question, but it actually stems from a misunderstanding of history and economics. The surprising truth is that poverty isn’t the puzzle; it’s the norm. Throughout most of human history, poverty has been the default condition. Even historical elites lived in conditions that would be considered shockingly deprived by today’s standards in developed nations.

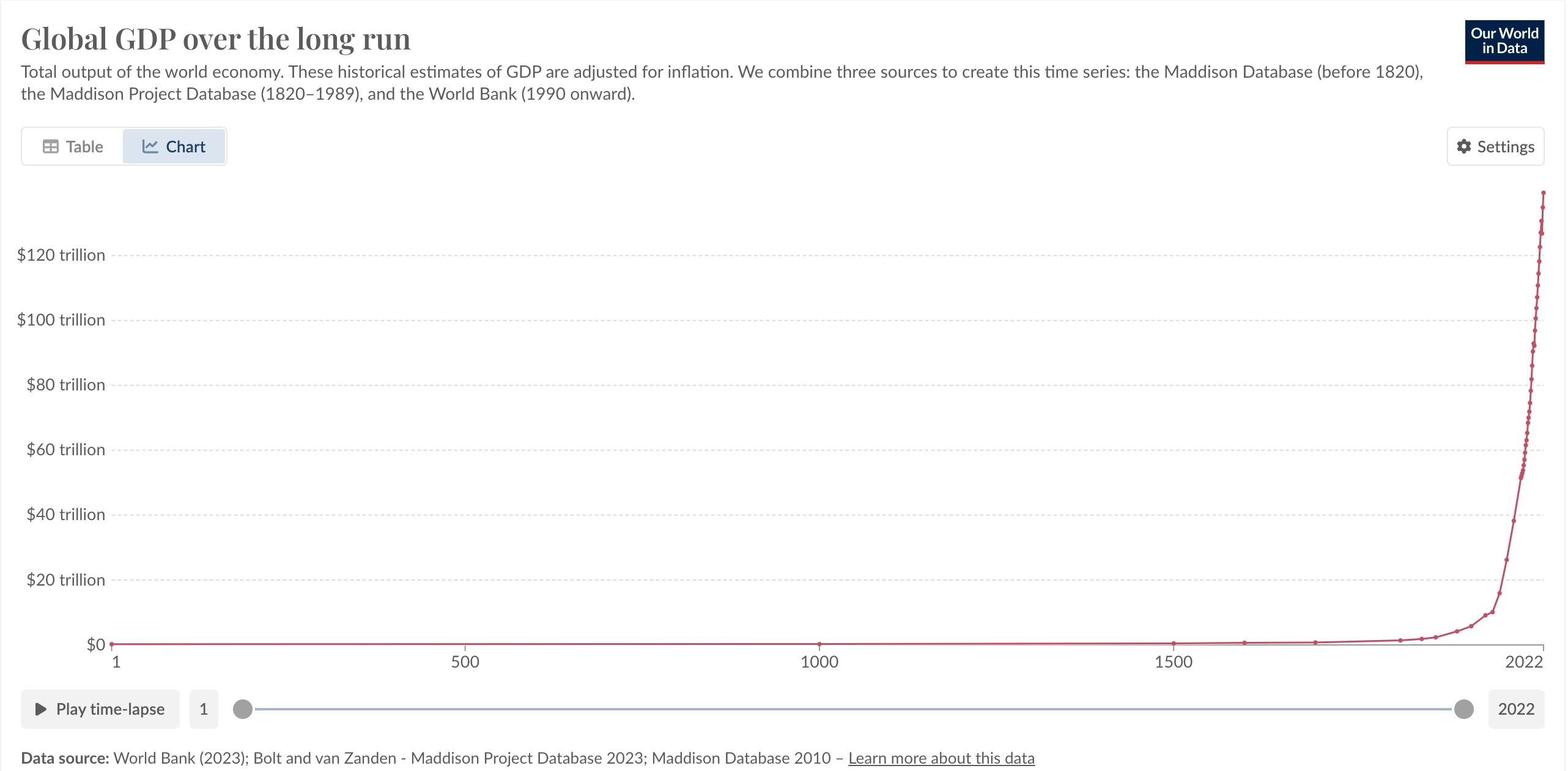

Consider the historical trajectory of global GDP. For millennia, economic growth was stagnant. This flat line represents widespread, inescapable poverty. It’s easy to fall into poverty. The real question, as Adam Smith pointed out, isn’t “why poverty?”, but “why wealth?”. Wealth, not poverty, is the anomaly that demands explanation.

Wealth creation is a recent phenomenon, driven by increased productivity and complex systems. It relies on fragile institutions and incentives: property rights, innovation-driven cultures, the rule of law, and open markets. These conditions are not naturally occurring.

In affluent societies like the UK, poverty can appear puzzling. Against a backdrop of prosperity, it’s natural to question why pockets of poverty persist. However, failing to recognize wealth as the true enigma leads to a distorted understanding of the world. Poverty becomes seen as an aberration requiring blame, rather than the baseline humanity reverts to without specific structures in place.

Explanatory Inversions: Why Our Intuitions Mislead Us

Joseph Heath, in Cooperation and Social Justice, discusses “explanatory inversions”. This concept highlights the difference between common sense and a scientifically informed worldview. Explanatory inversions occur when new discoveries shift our understanding of what needs explaining.

Heath uses social deviance as an example. Common sense asks, “Why Do People commit crime?”. Yet, criminal motivations like anger or greed are widespread. For every person who acts on these impulses criminally, many more do not. The “root causes” of crime are simply the potential benefits of criminal acts. People rob banks because that’s where money is.

This leads to an explanatory inversion: it’s not crime that needs explaining, but law-abiding behavior. Why do most people not commit crimes, even when it might be in their self-interest?

Common sense overlooks the complex institutional arrangements that ensure our compliance. We take for granted the systems that promote law-abidingness, making it difficult to grasp why more people don’t break the law more often. This example illustrates a broader explanatory inversion regarding human cooperation.

Why Do People Cooperate? The Puzzle of Collaboration

Human societies are built upon complex cooperation. Cooperation often feels natural. We join groups, build relationships, and help each other. Yet, cooperation is fundamentally perplexing. The benefits of cooperation can be undermined by those who take without contributing (free-riding).

It seems obvious that people will collaborate when it benefits them. However, individuals often benefit more by free-riding on others’ efforts. This can lead to a breakdown of cooperation, leaving everyone worse off. Cooperation is inherently challenging. History is filled with failures of cooperation, even when collaboration seems beneficial.

Therefore, the real question isn’t “why do people fail to cooperate?”. Failure is expected. The true puzzle is “why do people sometimes achieve large-scale cooperation?”. How do we incentivize and encourage collaboration among competitive individuals, overcoming self-interest and collective action problems?

From an evolutionary perspective, human cooperation beyond close relatives is unique. From a social science viewpoint, assuming rational self-interest, cooperation is also surprising.

Many people underestimate the complexity of cooperation, assuming it’s automatic when beneficial. Some even react negatively to the idea that altruism and cooperation are puzzling, like philosopher Susan Neiman’s critique of evolutionary psychology’s “problem of altruism.”

Neiman’s view reflects common sense, but common sense is often pre-scientific and incorrect. Just as we don’t rely on intuition in physics, we shouldn’t solely trust it to understand society.

Social Epistemology’s Explanatory Inversion: Why Truth, Not Falsehood, Needs Explanation

Social epistemology, the study of knowledge and belief in society, also needs an explanatory inversion. Many in this field focus on “Why do people believe false things?”. This question drives Marxist ideology critiques and modern research on misinformation. They ask why people (often “other people”) hold false beliefs.

While not without merit, this question is superficial. The deeper question is “Why do people sometimes form true beliefs?”. Truth, in social epistemology, is not the default.

Why Isn’t Truth the Default? The Role of Mediated Information

Walter Lippmann wrote, “The truth about distant or complex matters is not self-evident.” Our mental representations don’t automatically mirror reality. This is often overlooked in discussions of misinformation.

In modern societies, our understanding of reality is heavily mediated by trust, testimony, and interpretation. Consider complex topics like economics, crime rates, or climate change. Our knowledge comes from others – reports, books, opinions, and media. We rely on simplified mental models to process this information.

This process is rife with potential for error, even for rational individuals. We are also influenced by pre-scientific intuitions, cognitive biases, and self-serving motives. Those who provide us information are similarly fallible and biased. Some are intentionally deceptive, but most are simply affected by similar biases.

For these reasons, truth isn’t the default outcome of belief formation, especially regarding matters beyond our direct experience. Ignorance and misperceptions are the default states, much like poverty throughout history. The puzzle is how humans sometimes achieve accurate perceptions despite these obstacles.

Why Do People Believe Misinformation? Overlooking the Sources of Error

Why do many social epistemologists focus on “Why do people believe misinformation?” as the central question? One reason is “naive realism.” We often unconsciously assume our perception is a direct, unbiased reflection of reality. If truth is self-evident, then false beliefs seem inexplicable – those who hold them must be irrational or malicious.

Another deeper reason is taking knowledge for granted. In affluent, liberal societies, we benefit from the scientific revolution and Enlightenment ideals. Centuries of cultural and institutional development have aimed to overcome sources of ignorance.

Norms and Institutions: The Fragile Foundations of Knowledge

Norms: The Shift Towards Reason

A key part of this inheritance is a normative shift. The Enlightenment promoted applying reason and evidence to our beliefs, even about abstract concepts. Many in liberal societies now take this norm for granted. While motivated reasoning exists, it’s often seen as shameful. People strive to appear rational and objective truth-seekers.

This value system isn’t universal. Historically, worldviews were often shaped by identity, tribalism, and social cohesion, not truth. The Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason was radical. Even today, a significant minority in Western societies don’t believe beliefs should be based on evidence.

The expectation of rational justification for beliefs is also a relatively recent norm. Bertrand Russell’s assertion that “it is undesirable to believe a proposition when there is no ground whatsoever for supposing it is true” was not a platitude. It was a revolutionary idea challenging the common practice of belief without evidence. Russell believed adopting this norm could transform society.

This emphasis on reason extends to resolving disagreements. Instead of violence, rational persuasion is encouraged.

Institutions: Structures for Truth-Seeking

Alongside normative shifts, radical institutional changes have occurred. Science itself is an institution. It’s a status game where scientists compete for recognition through discoveries and knowledge advancement. This contrasts with historical contexts where novel ideas were often suppressed.

Science’s power lies in its method of validating discoveries and resolving disputes. It prioritizes empirical evidence over abstract philosophy. Science has developed elaborate norms, procedures, and institutions – journals, universities, peer review, funding – for knowledge generation and validation.

The replication crisis highlights the imperfections of these systems. Even institutions designed for knowledge creation often fall short. The same applies to other knowledge-generating institutions like legal and journalistic systems. Despite flaws, their success in producing and disseminating reliable information is remarkable.

Why Do People Take Knowledge for Granted? The Illusion of Epistemic Wealth

Just as wealth is often taken for granted in affluent societies, so is knowledge. Centuries of normative and institutional development have created an environment where reliable knowledge about complex issues is accessible.

Many of us can accurately understand vaccines, economic trends, and evolutionary history. From this perspective, misinformation and ignorance seem surprising. In an age of potential epistemic wealth, pre-scientific beliefs and conspiracy theories appear baffling.

However, in a deeper sense, this situation is not surprising. The truly remarkable aspect of modern societies is the degree to which accurate beliefs are formed about complex issues. Without this understanding, we risk seeing ignorance as the aberration, rather than recognizing the fragile and impressive achievement of widespread knowledge.

Why Does This Matter? Reorienting Our Understanding of Belief

The modern focus on “misinformation” is often historically shallow. There was no past “truth era.” History is filled with misinformation, conspiracy theories, and biased narratives.

Focusing solely on misinformation is explanatorily weak. Truth is not the default. Recognizing this shifts our approach to social epistemology.

First, it demands intellectual humility. Those claiming to know the truth, including misinformation experts, should acknowledge the numerous sources of error in human judgment beyond just “misinformation.”

Second, it reveals that misinformation and related phenomena are not deviations from a “truthful” norm. They are the default state that societies revert to without robust epistemic norms and institutions.

The real challenge is not just combating misinformation, but strengthening and maintaining the fragile norms and institutions that support truth-seeking and knowledge creation. Building trust in these systems is paramount for navigating the epistemic challenges of the 21st century.