The still of the night is often punctuated by a distinctive and somewhat eerie sound – the hoot of an owl. This nocturnal serenade, both familiar and mysterious, begs the question: Why Do Owls Hoot? These captivating birds of prey, with their large eyes and silent flight, use a variety of vocalizations, but their hoot is perhaps the most iconic and serves several crucial purposes in their lives.

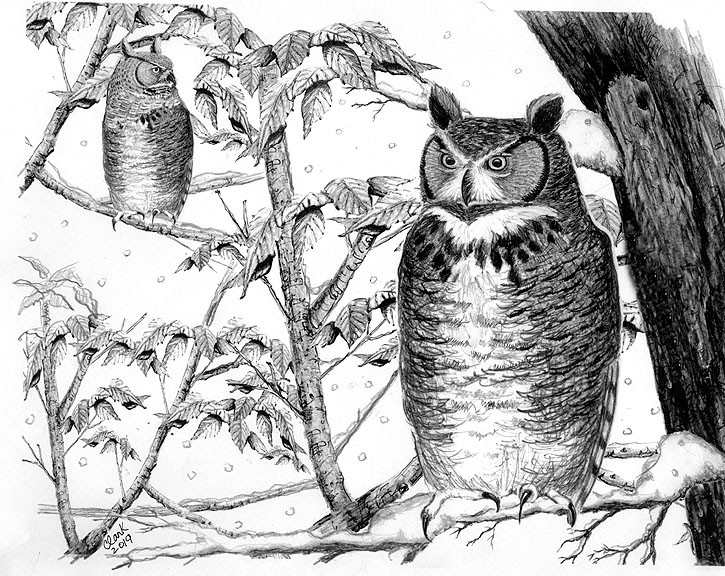

Great Horned Owl perched on a tree branch at night, calling out with open beak

Great Horned Owl perched on a tree branch at night, calling out with open beak

The Language of Owls: More Than Just “Who Cooks For You?”

While the classic “who cooks for you, who cooks for you all?” hoot of the Barred Owl might be a recognizable sound, owl vocalizations are far more complex than a simple question. Hooting is a primary form of communication for owls, serving as a vital tool for social interaction, especially for species like the Great Horned Owl. These adaptable and widespread owls, known for their prominent ear tufts (which are actually feathers, not ears), are often the culprits behind the nighttime hoots many people hear.

Pair Bonding: Strengthening the Relationship Through Song

For owls, particularly species like Great Horned Owls that typically mate for life, hooting plays a significant role in strengthening the pair bond. These nocturnal birds often engage in “duets,” where the male and female call back and forth to each other. This vocal exchange helps reinforce their commitment to one another and maintain their lifelong partnership. Think of it as a unique form of avian affection, a serenade that’s far more practical for survival in the wild than romantic gestures like gift-giving.

Territorial Declarations: “This is My Turf!”

Beyond strengthening bonds, hooting is also a powerful way for owls to establish and defend their territory. Owls are territorial creatures, and they need to secure a hunting ground to ensure they have enough food to survive and raise their young. Their hoots act as a clear message to other owls in the vicinity: “This area is occupied!” Instead of building fences or putting up signs like humans, owls use their resonant voices to broadcast their ownership, minimizing the need for physical confrontations and efficiently managing resources within their habitat.

Decoding the Hoot: What Are Owls Saying?

The hooting of owls isn’t just a random noise; it’s a structured communication with nuances. Consider the Great Horned Owl’s duet: typically, the female initiates the call with a series of hoots, often six or seven in a row. She then pauses, waiting for the male’s response. After a short interval, the male will reply with his own series of hoots, usually around five. Interestingly, despite the male Great Horned Owl being smaller than the female, his hoots are typically lower in pitch – sometimes described as being a “major third apart.”

As the pair continues their vocal exchange, the intensity and tempo can increase. The intervals between hoots shorten, and the duet can become more rapid, eventually reaching a point where the male may even start hooting before the female has finished her call. This synchronized hooting, while perhaps seemingly chaotic to human ears, represents a heightened state of communication and reinforces their bond and territorial claim.

Timing is Everything: Why Winter Hooting?

While owls can hoot throughout the year, you might notice an uptick in hooting activity during the winter months, especially for Great Horned Owls. This is because Great Horned Owls are early breeders. Unlike songbirds that wait for the spring abundance of insects, Great Horned Owls nest in late winter. This timing is strategically linked to food availability. Owl chicks are carnivorous and require a substantial amount of meat to grow. Hunting is often easier in late winter and early spring before dense foliage emerges, providing less cover for prey animals like rodents, rabbits, and other small mammals, ensuring a plentiful food supply when the owlets hatch.

Beyond the Hoot: Other Owl Sounds

While the hoot is the most well-known owl sound, these birds possess a diverse repertoire of vocalizations. Depending on the species and situation, owls might also squawk, screech, scream, whistle, or even snap their bills. These sounds can be used for various purposes, from expressing alarm or aggression to begging for food (in the case of young owls). Each sound contributes to the rich soundscape of the nocturnal world and the complex communication methods of these fascinating birds.

In conclusion, the hoot of an owl is far more than just a sound in the night. It’s a language, a declaration, and a vital tool for survival. Whether it’s strengthening pair bonds, defending territory, or simply communicating across distances, understanding why owls hoot unveils a deeper appreciation for the intricate lives of these nocturnal hunters and the hidden conversations that fill the darkness.