Introduction

Understanding the reactivity of elements is fundamental to grasping chemical behavior. Nonmetals, in particular, exhibit fascinating trends in their reactivity as we move up a group in the periodic table. Take the halogens (Group 17) as a prime example: fluorine is explosively reactive, while iodine is significantly less so. But what’s the underlying reason for this increased reactivity as we ascend a group of nonmetals? While it might seem counterintuitive at first glance, the answer lies in a combination of factors, with electron affinity playing a crucial role, albeit in a complex interplay with other periodic properties.

To unravel this phenomenon, we must first understand electron affinity itself. Electron affinity is defined as the energy change that occurs when an electron is added to a neutral atom in the gaseous phase to form a negative ion. Essentially, it quantifies an atom’s likelihood of gaining an electron. This energy change can be either exothermic (energy released, negative value) or endothermic (energy absorbed, positive value). For most nonmetals, the first electron affinity is exothermic, indicating a favorable attraction for an additional electron.

Delving into Electron Affinity: First and Second Affinities

When we talk about electron affinity, it’s important to distinguish between first and subsequent electron affinities.

First Electron Affinity: This refers to the energy change when a neutral atom gains one electron. For nonmetals, this process typically releases energy because they are eager to achieve a stable electron configuration by gaining electrons. Therefore, first electron affinities of nonmetals are generally negative.

X (g) + e⁻ → X⁻ (g) (Energy Released, Negative Electron Affinity)Second Electron Affinity: This is the energy change when a negative ion gains another electron. Adding a second electron to an already negatively charged ion requires energy to overcome the electrostatic repulsion. Consequently, second electron affinities are always positive, indicating an endothermic process.

X⁻ (g) + e⁻ → X²⁻ (g) (Energy Required, Positive Electron Affinity)While ionization energy focuses on the formation of positive ions, electron affinity is its negative ion counterpart. It’s particularly relevant for Group 16 (chalcogens) and Group 17 (halogens) elements, which readily form negative ions.

Electron Affinity Trends: Metals vs. Nonmetals

Electron affinity exhibits distinct trends across the periodic table, particularly when comparing metals and nonmetals.

Metals: Metals generally have lower electron affinities. Adding an electron to a metal atom often requires energy (endothermic or less exothermic). This is because metals readily lose electrons to form positive ions (cations) and achieve a stable electron configuration. Their valence electrons are loosely held due to a weaker effective nuclear charge and larger atomic radii, making them less inclined to attract additional electrons.

Nonmetals: Nonmetals, on the other hand, possess higher electron affinities. Gaining electrons for nonmetals is typically an exothermic process. This is attributed to their atomic structure:

- Higher Effective Nuclear Charge: Nonmetals have a greater effective nuclear charge compared to metals in the same period. This stronger positive charge from the nucleus attracts incoming electrons more strongly.

- More Valence Electrons: Nonmetals have more valence electrons, and gaining electrons helps them achieve a stable octet configuration, making electron gain energetically favorable.

- Smaller Atomic Radii: Valence shells in nonmetals are closer to the nucleus, leading to a stronger attraction for incoming electrons.

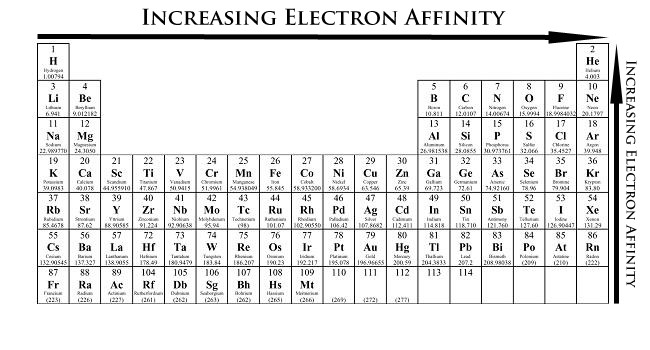

Periodic Table showing Electron Affinity Trend

As depicted in the periodic table trend, electron affinity generally increases across a period from left to right (becoming more negative) and decreases down a group (becoming less negative).

Periodic Patterns in Electron Affinity

The trends in electron affinity across periods and down groups are governed by fundamental factors:

Across a Period (Left to Right): Electron affinity generally increases (becomes more negative). As we move across a period, the effective nuclear charge increases, and atomic radius decreases. Electrons are added to the same energy level but experience a stronger nuclear pull, resulting in a greater release of energy when an electron is gained.

Down a Group (Top to Bottom): Electron affinity generally decreases (becomes less negative). While the nuclear charge increases down a group, the effect is counteracted by two primary factors:

- Increased Atomic Radius: Valence electrons are further from the nucleus in larger atoms down the group. The attraction between the nucleus and an incoming electron weakens with distance, resulting in less energy release.

- Increased Shielding: As we descend a group, the number of inner electron shells increases, leading to greater shielding of the valence electrons from the nucleus. This shielding effect reduces the effective nuclear charge experienced by an incoming electron, diminishing the attraction.

It’s crucial to note that the trend down a group is not always perfectly smooth, and anomalies exist, as we’ll explore with fluorine.

Figure 1: Periodic Variation of Electron Affinity with Atomic Number. Note both negative and positive values.

Example: Group 1 and Group 17 Trends

Let’s examine specific examples from Group 1 (alkali metals) and Group 17 (halogens) to illustrate these trends:

Group 1 Electron Affinities (kJ/mol):

- Lithium (Li): -60

- Sodium (Na): -53

- Potassium (K): -48

- Rubidium (Rb): -47

- Cesium (Cs): -46

As we descend Group 1, electron affinities become less negative, indicating a decreased tendency to gain electrons.

Group 17 Electron Affinities (kJ/mol):

- Fluorine (F): -328

- Chlorine (Cl): -349

- Bromine (Br): -324

- Iodine (I): -295

In Group 17, we observe a general decrease in electron affinity down the group, with chlorine having the most negative value, and fluorine exhibiting a slight anomaly.

The Fluorine Anomaly: Repulsion Matters

Fluorine, despite being at the top of Group 17, has a slightly less negative electron affinity than chlorine. This deviation from the expected trend arises from fluorine’s exceptionally small atomic size.

While the incoming electron in fluorine experiences a strong nuclear attraction due to its position at the top of the group, it also encounters significant electron-electron repulsion in the compact 2p subshell. Fluorine’s small size means its valence shell is already electron-dense. Adding another electron creates substantial repulsion, which counteracts some of the nuclear attraction, leading to a slightly less exothermic electron affinity compared to chlorine.

Chlorine, being larger, provides more space in its 3p subshell, reducing electron-electron repulsion and resulting in a more negative electron affinity. A similar anomaly is observed between oxygen and sulfur in Group 16.

Reactivity Up a Group: Beyond Electron Affinity

Now, let’s circle back to our initial question: Why Do Nonmetals Get More Reactive Up A Group?

While electron affinity provides valuable insights, it’s not the sole determinant of reactivity. In fact, the trend in electron affinity alone might suggest that reactivity should decrease up Group 17, as electron affinity becomes less negative for fluorine compared to chlorine. However, the opposite is true: fluorine is far more reactive than chlorine.

The increased reactivity of nonmetals as you move up a group, particularly in the halogens, is governed by a combination of factors:

-

Electronegativity: Electronegativity, the ability of an atom to attract electrons in a chemical bond, increases as you move up a group. Fluorine is the most electronegative element. Higher electronegativity means a stronger tendency to attract electrons in reactions, contributing to greater reactivity.

-

Ionization Energy: Ionization energy, the energy required to remove an electron, increases up a group. While seemingly contradictory to electron affinity, higher ionization energy in nonmetals up a group means they hold onto their own electrons more tightly, further reinforcing their tendency to gain electrons from other reactants.

-

Bond Dissociation Energy (for diatomic nonmetals like halogens): The bond energy of X-X diatomic molecules (like F₂, Cl₂, Br₂, I₂) decreases as you move up Group 17 from chlorine to fluorine. Fluorine has an unexpectedly weak F-F bond due to lone pair repulsion in its small diatomic molecule. This lower bond energy means less energy is required to break the F-F bond, making fluorine more readily available for reactions.

-

Hydration Enthalpy (for halide ions): The hydration enthalpy of halide ions (X⁻) becomes more negative (more exothermic) as you move up Group 17. Smaller halide ions like F⁻ are more strongly hydrated due to a higher charge density, releasing more energy upon solvation in polar solvents like water. This increased stability of fluoride ions in solution contributes to fluorine’s higher reactivity in aqueous reactions.

In summary, while electron affinity provides a measure of an atom’s intrinsic attraction for an electron, the overall reactivity of nonmetals up a group is a complex interplay of electronegativity, ionization energy, bond dissociation energy, hydration enthalpy, and other factors. For halogens, the decreasing bond energy of X-X and increasing hydration enthalpy of X⁻ ions as you move up the group play a more dominant role in explaining the enhanced reactivity of fluorine compared to chlorine, bromine, and iodine, despite the slight anomaly in electron affinity for fluorine.

Conclusion

Understanding why nonmetals become more reactive as you move up a group requires considering multiple periodic trends beyond just electron affinity. While electron affinity provides valuable insights into an atom’s tendency to gain electrons, factors like electronegativity, ionization energy, bond strengths, and solvation energies are equally crucial in determining overall chemical reactivity. For nonmetals like halogens, the unique properties of fluorine, such as its high electronegativity and weak F-F bond, combined with favorable hydration of fluoride ions, drive its exceptional reactivity at the top of Group 17, showcasing the nuanced and multifaceted nature of periodic trends in chemistry.

Practice Problems

- Is energy released or absorbed when an electron is added to a nonmetal atom?

- Explain why nonmetal atoms generally have a greater electron affinity than metal atoms.

- Why are atoms with a low electron affinity more likely to lose electrons?

- Describe the trend in electron affinity as you move down a group in the periodic table and explain the reasons behind this trend.

- Why do nonmetals tend to gain electrons in chemical reactions?

- Explain why metals typically have low electron affinities.

Answers

- Energy is typically released (exothermic) when an electron is added to a nonmetal atom.

- Nonmetal atoms have a greater electron affinity than metal atoms due to their atomic structure: they have a higher effective nuclear charge, more valence electrons, and smaller atomic radii, all of which contribute to a stronger attraction for additional electrons.

- Atoms with a low electron affinity are more likely to lose electrons because they do not readily attract additional electrons. Their valence electrons are further from the nucleus and experience less nuclear pull, making it easier to remove electrons than to gain them.

- Electron affinity generally decreases (becomes less negative) as you move down a group in the periodic table. This is primarily due to increasing atomic radius and increased shielding effect. Valence electrons are further from the nucleus and experience less effective nuclear charge, reducing the attraction for an incoming electron.

- Nonmetals tend to gain electrons because they have more valence electrons and are closer to achieving a stable octet electron configuration. Gaining electrons is energetically favorable for them, releasing energy and leading to a more stable state.

- Metals typically have low electron affinities because they readily lose valence electrons to achieve a stable electron configuration. They have a weaker hold on their valence electrons and do not readily attract additional electrons; gaining electrons for metals often requires energy input.

References

- Petrucci, Harwood, Herring, Madura. General Chemistry Principles & Modern Applications. Prentice Hall. New Jersey, 2007.

- Tro, Nivaldo J. (2008). Chemistry: A Molecular Approach (2nd Edn.). New Jersey: 2008.

- Myers, R. Thomas. “The periodicity of electron affinity.” J. Chem. Educ. 1990, 67, 307.

- Wheeler, John C. ” Electron Affinities of the Alkaline Earth Metals and the Sign Convention for Electron Affinity.” J. Chem. Educ. 1997 74 123.