Deer antlers are undeniably one of the most captivating features in the animal kingdom. Their unique form and annual cycle spark curiosity and fascination in anyone who has witnessed a majestic buck in its prime. The allure of antlers stems from their distinctiveness – no two sets are exactly alike, and their yearly growth and shedding is a remarkable biological phenomenon. So, let’s delve into the question: why do whitetail bucks shed their antlers each year?

As winter approaches, many nature enthusiasts venture into woodlands in search of shed antlers, those prized treasures left behind by bucks. To truly appreciate these finds, it’s essential to look beyond their points and curves and understand the incredible animal that grew them. This leads us to explore not just “how” to find sheds, but also the fundamental “why” behind this natural process.

Antler shedding marks the end of one antler’s life cycle and the beginning of the next. Shed hunting has gained considerable popularity, and resources abound on techniques for how to find antlers. However, understanding the deeper questions, such as “why do deer have antlers instead of horns?”, “why might a buck shed earlier than expected?”, or “what biological mechanisms cause antler shedding?” provides a richer appreciation for this natural wonder. Let’s uncover the answers to these intriguing questions and more.

What are Antlers and How are They Different from Horns?

Antlers and horns, while both head adornments found in certain animal species, are fundamentally different in their composition and life cycle. Understanding these distinctions is key to appreciating the unique nature of antlers. Firstly, antlers are made of bone, a solid, living tissue. In contrast, horns possess a core of living bone that is covered by a sheath of keratin. Keratin is a tough, fibrous protein, the same material that forms our fingernails and hair. With the notable exception of pronghorn in North America, animals with horns typically retain them throughout their lives, never shedding them. Antlers, however, are shed and regrown annually, a process unique to deer and their relatives. Furthermore, antlers are characterized by their branched structure, or forks, while horns generally lack branching. Finally, horns grow continuously from their base, meaning the oldest part of the horn is at the tip. Antlers, during their growth phase, extend from their tips, encased in a soft, vascularized tissue known as velvet.

The growth of antlers is a remarkable process that typically occurs from late spring through summer. During this period, a buck’s body undergoes a significant physiological shift. To fuel rapid antler development, the deer’s body extracts substantial amounts of minerals, particularly calcium and phosphorus, from its skeleton. This mineral mobilization means that during antler growth, a buck is in a temporary state of osteoporosis, a condition characterized by decreased bone density. Once the antler growth season concludes, these mineral reserves are replenished in the skeleton. This internal mineral sourcing is necessary because a deer cannot absorb minerals quickly enough through its digestive system to meet the intense demands of antler growth, which is recognized as the fastest-growing tissue in any mammal.

The Energetic Investment: Why Antlers Instead of Permanent Horns?

The annual cycle of growing and shedding antlers appears to be an energetically expensive undertaking. Consider that bucks invest significant resources to grow several pounds of solid bone on their heads each year, only to discard them after a few months. In the animal kingdom, energy efficiency is paramount for survival and reproduction. An animal must consistently acquire more energy than it expends to thrive and, crucially, reproduce. This raises a compelling question: why have deer evolved to grow antlers annually, instead of developing permanent horns, which would seem to be a more efficient energy investment?

The prevailing scientific theory suggests that antlers serve as a more sensitive and dynamic indicator of a buck’s overall health and fitness than permanent horns would be. From a biological standpoint, it is crucial for a doe to mate with a healthy and well-adapted buck. This maximizes the chances that her offspring will inherit beneficial traits, survive, and continue the species. Antlers play a vital role in this process through several mechanisms. Firstly, antler size is a key factor in determining the outcome of sparring matches between bucks. These contests establish dominance hierarchies, influencing access to breeding opportunities and ultimately affecting buck survival. Moreover, recent research from the Mississippi State Deer Lab indicates that does, when given a choice, tend to prefer breeding with bucks possessing larger antlers over those with smaller antlers.

While horn size could potentially serve similar functions in sparring and mate selection, as it does in other horned animals, antlers offer a more nuanced and responsive signal of a buck’s condition. For example, if a buck sustains multiple bone fractures due to injury, its body will prioritize healing the skeletal damage, diverting energy and resources away from antler growth. In such a survival-focused state, the buck’s antlers will likely be significantly smaller than they would be if he were in peak physical condition with ample skeletal resources available for antler development.

Conversely, if a buck breaks off a main beam during a sparring match, he will regenerate an entirely new set of antlers the following season. Horns, unlike antlers, do not regrow if damaged. If deer possessed horns, a buck with a broken horn would be permanently disadvantaged. In both of these scenarios, antlers prove to be superior to horns in providing an accurate and up-to-date reflection of a buck’s fitness. A buck in poor health will exhibit smaller antlers, while a healthy buck that experiences antler damage can recover and grow a new set, ensuring that antler size remains a reliable indicator of their current condition.

Ultimately, antlers serve a very specific and critical purpose in a buck’s life. They are far more than just ornamental crowns that attract hunters. Antlers are essential tools for sparring, defense against predators, and a visual display of dominance and fitness during the breeding season. They are, in essence, indispensable for successful deer reproduction.

Testosterone: The Master Regulator of Antler Shedding

The entire process of antler growth and shedding is meticulously controlled by hormones, with testosterone playing the central regulatory role. The seasonal fluctuations in testosterone levels in bucks are the primary drivers behind the antler cycle. Rising testosterone levels in late summer initiate the mineralization of the antlers, hardening them from velvet-covered structures into solid bone. Subsequently, testosterone also triggers the drying and shedding of the velvet, revealing the polished antlers beneath. Testosterone levels reach their peak during the rut, the deer breeding season. This surge in testosterone is responsible for the dramatic changes observed in bucks during this period, including swollen necks, heightened aggression, and a shift in focus from feeding to breeding.

Following the rut, as breeding activity subsides, bucks experience a significant drop in testosterone levels. This decline is the key trigger for the antler shedding process. While testosterone is the primary hormone governing these milestones in a buck’s antler and breeding cycle, it is itself influenced by other factors. The most important regulator of a whitetail deer’s annual rhythm is the sun. Photoperiod, or day length, serves as the environmental cue that signals a buck’s body to adjust testosterone production. As daylight hours shorten in the fall, this change in photoperiod prompts a decrease in testosterone, ultimately initiating antler shedding. Similarly, photoperiod regulates the doe’s reproductive cycle, signaling when it’s time to breed. Thus, day length is the ultimate environmental cue that orchestrates antler shedding in bucks.

However, factors beyond photoperiod can also influence testosterone levels and, consequently, antler shedding timing. For instance, late breeding opportunities can lead to sustained higher testosterone levels. “Late breeding does” may result from various situations, such as unsuccessful egg implantation after the initial breeding attempt, a doe fawn reaching sexual maturity later in the season, or occasionally a doe that was missed during the peak rut. If breeding opportunities persist, a healthy buck will maintain elevated testosterone levels to capitalize on these chances.

Conversely, a buck experiencing poor health or injury may undergo a sudden decrease in testosterone levels. This can occur when a buck is involved in a vehicle collision, sustains a non-fatal gunshot wound, or is injured during sparring. In these stressful scenarios, a buck’s body shifts into survival mode, prioritizing resource conservation over reproduction. This physiological stress triggers a rapid decline in testosterone, which in turn can induce premature antler shedding. Therefore, if a buck is observed shedding antlers unusually early, such as in November or December, it often indicates that the animal is under significant stress and is likely not in good health.

What Makes Antlers Drop?

While we understand that testosterone levels and ultimately photoperiod are responsible for initiating antler shedding, the precise mechanism of how antlers detach from the skull is a fascinating and complex process, further highlighting the unique nature of antlers.

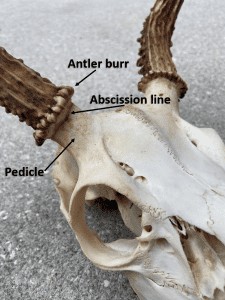

On a buck’s skull, there are two bony protrusions located above each eye socket. These protrusions are called “pedicles” and serve as the permanent anchors connecting a buck’s antlers to its skull. Pedicles are a lifelong component of a buck’s skeletal structure, and they gradually increase in diameter as the buck ages. At the base of each antler, where it meets the pedicle, is a bony ring known as the antler burr. The burr acts as a protective shield, safeguarding the delicate skin at the junction of the antler and pedicle.

Specialized cells called “osteoclasts” accumulate at the base of the antler, in the region between the burr and the pedicle. Osteoclasts are responsible for bone resorption, the process of breaking down bone tissue. As testosterone levels decline after the rut, these osteoclasts become activated and begin to actively erode the bone at the interface between the pedicle and the antler. This area of bone resorption is known as the “abscission line.” The osteoclast activity progressively weakens the abscission line until it can no longer bear the weight of the antler. Eventually, the connection gives way, and the antler detaches and sheds. The base of a shed antler typically exhibits tiny pits and an irregular surface, a result of the bone resorption that occurred along the abscission line. Following antler shedding, a scab forms over the exposed, bloodied pedicle, protecting it as the process of new antler growth begins the following spring.

Incredible Bones

Antlers undoubtedly deserve the fascination and admiration they garner from hunters and nature enthusiasts alike. Witnessing a magnificent buck or discovering its shed antlers in the woods is a reminder of the intricate and remarkable biological processes that create these incredible natural trophies. As you explore the outdoors in search of shed antlers, take a moment to appreciate the fascinating story behind how each antler grew and was ultimately shed, a testament to the wonders of nature.

Moriah Boggess is a Deer Biologist with the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission