We delve into a common question in the realm of nature and biology: why do honeybees meet their demise after stinging? It’s a question that sparks curiosity and reveals a fascinating, albeit grim, aspect of the honeybee’s life and defense mechanisms. When a honeybee stings, it’s not just an act of defense; it’s a suicidal mission. This article will explore the intricate reasons behind this self-destructive behavior, examining the anatomy of a honeybee stinger and the biological processes that lead to a bee’s death after stinging.

The act of stinging for a honeybee is far from simple. Unlike wasps or hornets that can sting multiple times, a honeybee’s sting is a one-time affair, ending in a gruesome death. As Eric Mussen, an apiculturist from the University of California at Davis, explains, “When a honeybee stings, it dies a gruesome death.” This dramatic consequence is due to the unique structure of the honeybee’s stinger.

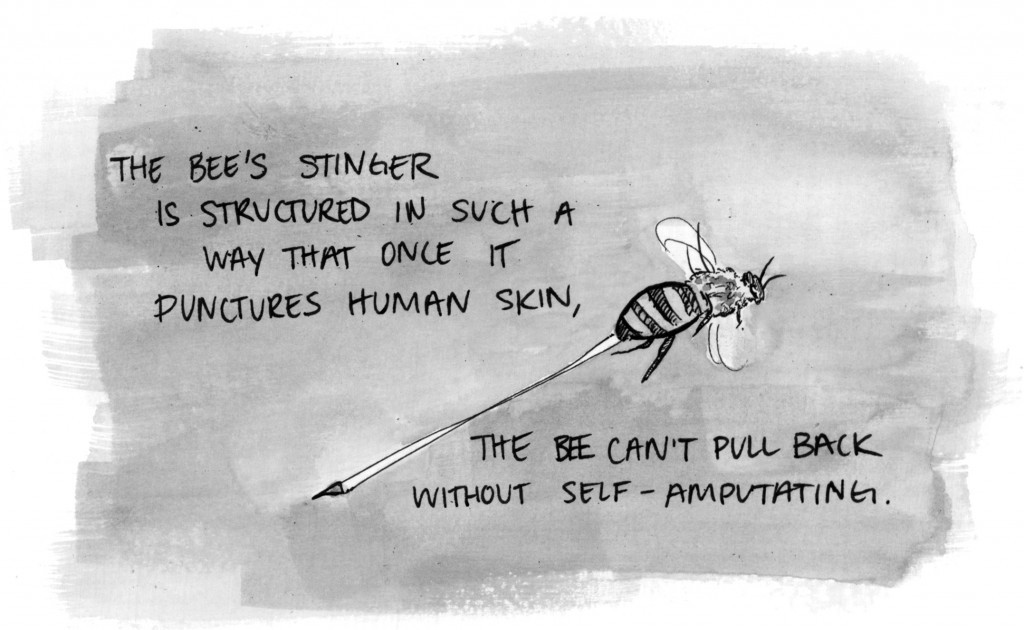

The honeybee stinger is not just a simple pointy object. It’s equipped with barbs, much like a harpoon, designed to lodge firmly into the skin of mammals. Imagine trying to remove a deeply embedded fishhook – that’s akin to what a honeybee faces when it attempts to withdraw its stinger from human skin. The stinger, functioning like a hypodermic needle as Mussen describes, is hollow and sharp. It features two rows of lancets, or saw-toothed blades, which are barbed and angled outwards.

When a honeybee stings, these barbed lancets penetrate the skin. According to Mark Winston, a biologist and author of “Bee Time: Lessons from the Hive,” these blades work in an alternating “scissoring” motion, effectively screwing the stinger deeper into the flesh. This screw-anchor mechanism ensures that the stinger is firmly lodged and difficult to remove.

The real tragedy for the bee occurs when it tries to fly away after stinging. Because the barbs are firmly anchored in the victim’s skin, the bee cannot simply pull the stinger out. Instead, as it attempts to free itself, the stinger remains stuck, and the bee ends up self-amputating. This process involves the honeybee rupturing its lower abdomen. As it pulls away, it leaves behind not just the stinger, but also a string of its digestive tract, muscles, glands, and the venom sac. This results in a significant and fatal abdominal rupture. As Mussen puts it, “It’s kind of like bleeding to death, except bees don’t have blood. It’s fake, clear insect blood.” This ‘bleeding’ and massive internal injury is what causes the honeybee to die shortly after stinging.

It’s crucial to note that this suicidal stinging behavior is unique to honeybees and, specifically, female worker bees. Honeybee colonies are structured around a queen, drones (males), and thousands of worker bees (infertile females). Worker bees are the defenders of the hive. They are essentially “disposable soldiers,” as their primary roles are to gather nectar, pollinate plants, and protect the colony. Only female worker bees possess stingers. The queen bee, the sole fertile female, can sting, but she typically only does so in fights against rival queens. Drones, being male, do not have stingers at all.

While wasps and bumblebees are often perceived as more aggressive, honeybees are generally docile and only sting when they feel threatened or when their hive is in danger. The alarm pheromone released with the venom, which, surprisingly, smells like bananas according to Mussen, signals danger to other bees in the vicinity, further emphasizing the defensive nature of stinging for honeybees. Unlike wasps or bumblebees that can sting repeatedly and survive, the honeybee’s single sting is a final act of defense, a sacrifice for the safety of the hive. As Mussen concludes, “A wasp or a bumblebee can sting again and again, but the honeybee only gets you once, and it’ll get you good.”