The French and Indian War, known in Europe as the Seven Years’ War, was a significant conflict in North American history. It stemmed from escalating tensions and disputes between Great Britain and France over territory and influence in the Ohio River Valley. This North American theater of the larger global war began with a series of critical incidents between 1753 and 1754, transforming simmering rivalry into open warfare. Understanding Why Did The French And Indian War Start requires examining these initial confrontations and the underlying imperial ambitions that fueled the conflict.

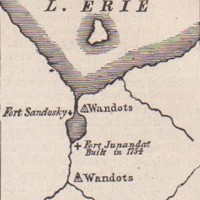

The Ohio River Valley became the primary point of contention. Both the French and British empires laid claim to this resource-rich region, vital for trade and expansion. To solidify their territorial claims and limit British influence, the French embarked on a strategy of constructing a line of forts. These fortifications stretched from Lake Erie southward towards the strategic forks of the Ohio River – the site of present-day Pittsburgh.

This assertive move by the French directly challenged the territorial aspirations of the British colonies, particularly Virginia, which also claimed dominion over the Ohio Valley. Robert Dinwiddie, the Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, viewed the French fort construction as a direct encroachment. In late 1753, he dispatched a young Major George Washington on a diplomatic mission. Washington’s objective was to deliver a message to the French commanders, demanding they dismantle their newly erected forts and withdraw from what Britain considered its territory.

Washington and his small contingent journeyed to Fort Le Boeuf, situated approximately 15 miles inland from the shores of Lake Erie in present-day Pennsylvania. He presented Governor Dinwiddie’s demands to Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre, the fort’s commander. While Saint-Pierre received Washington and his delegation with courtesy, he firmly rejected the British claims to the Ohio Valley. He asserted France’s prior claim and its determination to maintain its presence in the region. Returning to Virginia in early 1754, Washington reported the French refusal to Governor Dinwiddie.

The French commander’s defiant response was perceived by Dinwiddie and the Virginia legislature as an act of hostility and a clear indication of French intentions to aggressively pursue their territorial ambitions. Determined to counter the French moves, Dinwiddie authorized Captain William Trent of the Virginia militia to undertake a crucial mission. Trent was tasked with constructing a British fort at the forks of the Ohio River, a strategically vital location. Furthermore, Trent was instructed to forge alliances with the local Native American tribes, aiming to enlist their support against the French. Recognizing the escalating tensions, Dinwiddie also promoted George Washington to Lieutenant Colonel and entrusted him with leading a military expedition to compel the French to abandon their forts by force if necessary.

As both European powers mobilized their military resources and engaged in strategic fort construction, a parallel effort unfolded to secure the allegiance of the American Indian populations residing in the contested Ohio Valley. Among these groups, the Mingoes held a prominent position. They were affiliated with the Iroquois Confederation, a long-standing ally of Great Britain. British officials asserted that the Iroquois Confederacy had bestowed upon a Native American leader named Tanaghrisson the title of ‘Half-King,’ granting him authority over the Mingoes and other indigenous communities under Iroquois influence.

However, the reality of Native American allegiances and perspectives was far more complex. Many indigenous groups in the upper Ohio Valley harbored deep concerns about the westward expansion of British colonists and their encroachment upon native lands. They did not readily acknowledge either British or Iroquois authority over their territories. Although some harbored historical grievances against the French from previous conflicts and were wary of French power, many Ohio Valley Indians came to view a French alliance as the lesser of two evils compared to the perceived threat of British colonization. Consequently, they demonstrated a greater inclination to cooperate with the French, providing them with valuable intelligence regarding British movements and, in some instances, contributing manpower to French forces.

Capitalizing on intelligence provided by their Native American allies, the French swiftly learned of the British fort construction led by William Trent. French forces moved decisively, arriving at the forks of the Ohio on April 17, 1754, and compelling the outnumbered British contingent to surrender. The French then proceeded to demolish the unfinished British fort and, in its place, constructed a significantly more formidable fortification, named Fort Duquesne.

Further south in southwestern Pennsylvania, George Washington, accompanied by Tanaghrisson and their forces, encountered a small encampment of French soldiers on May 24, 1754. In a surprise attack initiated by Washington’s troops, a brief but consequential skirmish ensued. During the aftermath of the fighting, the wounded French commander, Ensign Joseph de Jumonville, attempted to communicate through interpreters. He asserted that his French detachment was on a peaceful mission to deliver a warning to British forces about their unauthorized incursions into French-claimed territory.

Accounts of the Jumonville incident vary, particularly regarding the crucial intervention of Tanaghrisson. It appears that Tanaghrisson, driven by a deep-seated personal animosity towards the French stemming from past war experiences, deliberately intervened during the parley and killed the wounded Jumonville. This act dramatically escalated tensions. Anticipating a forceful French response, Washington ordered the hasty construction of a rudimentary defensive structure, later named Fort Necessity, and prepared for an expected counterattack. Indeed, a combined French and Indian force soon arrived, overwhelming Washington’s troops and compelling his surrender on July 3, 1754.

News of Washington’s defeat at Fort Necessity reached Lieutenant Governor Dinwiddie, who immediately relayed the alarming developments to his superiors in London and appealed to neighboring colonies for military assistance. However, only North Carolina offered a response, but they declined to allocate resources beyond their own colonial borders. In contrast, British Prime Minister Thomas Pelham-Holles, the Duke of Newcastle, reacted decisively to the unfolding crisis. He formulated a plan for a swift military strike against the French forts in North America before they could be reinforced, recognizing the urgency of the situation. King George II promptly approved Newcastle’s strategy, authorizing the dispatch of General Edward Braddock to lead a military expedition to seize key French frontier forts.

However, certain political factions within the British government advocated for a more comprehensive and larger-scale war against France. They publicly revealed Newcastle’s initial limited plan and significantly expanded its scope. Braddock’s command was augmented with more substantial forces, and the fractious North American colonies were mandated to provide additional troops and logistical support for the impending campaign against the French. Once these expanded war plans became public knowledge, the French government responded swiftly. They initiated the deployment of significant reinforcements to North America and intensified diplomatic efforts to isolate Great Britain on the European stage, seeking to solidify alliances with traditional rivals of the British. With military mobilizations underway on both sides of the Atlantic and diplomatic maneuvering escalating, the slide into full-scale war became irreversible. The incidents of 1753-54, therefore, reveal why did the French and Indian War start: a culmination of territorial disputes, escalating military actions, and a failure of diplomacy, all set against a backdrop of imperial rivalry.