The medieval indulgence, a document offered by the Church in exchange for money and purported to guarantee the remission of sins, became a central point of contention for Martin Luther. It was the blatant abuse of this practice that ignited the flames of the Protestant Reformation, sparked by Luther’s groundbreaking 95 Theses. Martin Luther (1483-1546) vehemently argued that the sale of indulgences was not only unbiblical but also fundamentally undermined the Church’s authority as God’s representative on Earth. Why Did Martin Luther Object To Indulgences so strongly? The answer lies in understanding the historical context of indulgences, their evolution, and Luther’s theological convictions.

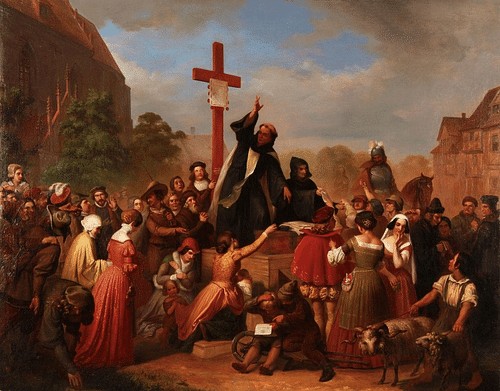

Indulgence Sales by Johann Tetzel: A depiction of Johann Tetzel, an indulgence seller, showcasing the controversial practice that Martin Luther strongly opposed.

Indulgences were not a novel concept in the medieval Church. They were rooted in the idea of the ‘treasury of the Church,’ a spiritual reservoir believed to contain the surplus merits of Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, saints, and other exceptionally virtuous individuals. This treasury, according to Church doctrine, could be accessed by ordinary Christians to reduce their time in purgatory or to remit the earthly penalties for their sins. Initially, the purchase of an indulgence was linked to genuine acts of penitence. However, by the time of Martin Luther, the monetary contribution often overshadowed the spiritual aspect, and paying for the writ was frequently deemed sufficient for absolution.

Martin Luther had voiced his concerns about indulgences in his sermons even before 1517. However, the arrival of the indulgence seller Johann Tetzel (c. 1465-1519) in his region in 1516 acted as the catalyst for more decisive action. In response to Tetzel’s activities, Luther penned his 95 Theses in 1517. These theses were intended as points for scholarly debate concerning indulgences. Luther sent a copy to Albrecht von Brandenburg, the Archbishop of Mainz, who, in turn, forwarded it to Pope Leo X. Simultaneously, Luther’s supporters translated the 95 Theses from Latin into German and disseminated them widely through printing. These parallel actions transformed Luther’s academic disputations into a direct challenge to the Church’s authority. The Church’s subsequent attempts to silence Luther only served to further radicalize his position, propelling him and Europe toward the seismic shift of the Protestant Reformation.

The Medieval Indulgence System: Origins and Evolution Before 1400

To fully grasp why Martin Luther objected to indulgences, it’s crucial to understand their historical development. The earliest seeds of the indulgence can be traced back to the 3rd century, during the reign of Roman Emperor Decius (249-251). Decius’ persecution of Christians demanded that they provide written proof (libelli) of having sacrificed to Roman gods. Christians who complied, denying their faith, later sought readmission into the Church. In some cases, these ‘lapsed’ individuals presented writs, vouched for by martyrs or respected deceased members of the church, affirming their Christian faith. These writs were accepted, marking what is considered the earliest form of indulgence – a policy of leniency based on the spiritual merit of others.

Pope Urban II: An image of Pope Urban II, who in 1095, declared indulgences for participants in the First Crusade, marking a significant expansion in their use.

While the theological underpinnings of indulgences were not fully developed at this stage, the acceptance of these writs implied the transfer of spiritual merit. The ‘lapsed’ were still required to perform penance, but the writ served as an assurance to the early Church of their worthiness for readmittance. Scholar John Bossy explains that indulgences evolved from the earlier system of public penance, representing the “remission, diminution, or conversion of the penal satisfaction imposed on the sinner” during readmission to the Church. Furthermore, it included the Church’s promise to offer prayers (suffragia) to God for the sinner’s reconciliation.

The term “indulgence,” meaning “to be kind to” or “indulgent of,” reflected the understanding that it was evidence of God’s willingness to forgive, facilitated by the spiritual merit of another. This understanding laid the foundation for the concept of the ‘treasury of merit’ (or ‘treasury of the Church’). This doctrine posited that the accumulated spiritual merit from Christ, the Virgin Mary, saints, and martyrs could be drawn upon by those in need for their own salvation.

However, even with indulgences, sinners were still expected to demonstrate their worthiness of forgiveness through penitential acts. The specific acts were determined by a priest after confession. Sometimes, the required penance was impractical due to age, health, or social duties. In such instances, a financial fine was imposed instead, with the funds directed towards charitable causes such as the construction and upkeep of churches, hospitals, and orphanages.

A significant expansion of indulgences occurred in 1095 when Pope Urban II declared indulgences for those participating in the First Crusade (1095-1102). Participation in the Crusade was considered absolution for all sins. For those unable to join the Crusade, indulgences could be obtained through monetary contributions. Figures like Saint Albertus Magnus (c. 1200-1280) and Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) further elaborated on the treasury of merit, providing theological justification for indulgences as a tangible expression of a spiritual exchange, where spiritual ‘points’ were gained in return for penitential acts, or their monetary equivalent.

The Growing Abuse of Indulgences Post-1400

The nature of indulgences underwent a significant transformation after 1400 as their sale became increasingly vital to the medieval Church’s finances. Congregants began to notice a shift where monetary payment seemed to entirely replace genuine penance for the remission of sins. Pardoners, officials specifically appointed by the Church to sell indulgences, traveled from town to town, delivering dramatic sermons designed to frighten people into purchasing indulgences for themselves or for loved ones believed to be suffering in purgatory. Bossy notes this evolution:

By 1400, [indulgences] had become attached to a variety of works, of which the most important was the crusade, but including public improvements like bridge or church-building; it had become established that these works could be performed by proxy, or commuted for money; the granting of it had become in effect a papal monopoly; and in answer to the objection that sins could not be forgiven for which satisfaction had not been made, theologians like Aquinas had come up with the notion of the treasure of the Church. … Satisfactory penance due from one person could be made by another, provided the relation between the two parties was sufficiently intimate that what was done by one of them could be taken, by God and by the Church, as being done by the other.

The Church essentially presented a system where penance could be fulfilled either through traditional acts or through financial contributions. This monetary penance granted access to the treasury of merit. This merit could be applied in various ways: to oneself in the present life, saved for the afterlife to shorten purgatory, used to bypass purgatory altogether (for a sufficiently large sum), or even applied to deceased relatives and friends believed to be undergoing purification in purgatory.

The Devil Selling Indulgences: A satirical depiction of the Devil selling indulgences, highlighting the growing perception of corruption and abuse within the indulgence system.

Despite official Church condemnation of unscrupulous pardoners – like the Pardoner depicted in Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales – the Church continued to profit from the widespread sale of indulgences. Nobility also benefited, taking a share of the proceeds from sales within their territories. Reports sent to Rome were often falsified to underreport indulgence sales, with regional nobles often pocketing half or more of the actual revenue. This widespread financial motivation behind indulgences was a key factor in why Martin Luther objected to them so vehemently.

Johann Tetzel and the Indulgence Controversy: The Immediate Trigger

The Church’s policy of accepting monetary payments without requiring penitential acts intensified as indulgences grew in popularity. Indulgence salesmen became figures of public spectacle, offering a mix of entertainment and the promise of salvation. People willingly paid for indulgences, enticed by guarantees of immediate spiritual benefits, encapsulated in popular phrases like, “When the gold in the coffer rings, the rescued soul toward heaven springs” (or “When the money in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs”). The dramatic and emotionally charged performances of indulgence sellers drew large crowds eager to secure salvation. Scholar Lyndal Roper describes the scene:

No one compelled people to buy indulgences, but there was a huge market for them. When the indulgence-sellers arrived at a town the papal bull [the charter approving the indulgence, with the Pope’s lead seal affixed] would be carried about on a satin or golden cloth, and all the priests, monks, town council, schoolmaster, schoolboys, men, women, maidens, and children, all met it singing in procession with flags and candles. All the bells were rung, all the organs were played…the indulgence-seller was led into the churches and a red cross was erected in the middle of the church where the papal banner would be hung. So efficiently organized was the system that the indulgences were even printed locally on parchment that could be filled in with the name of the person on whose behalf they were purchased.

In 1516, Albrecht von Brandenburg, Archbishop of Mainz, secured Pope Leo X’s permission to sell indulgences in his region. Albrecht was deeply indebted to the Fugger banking family, who had financed his acquisition of his ecclesiastical office. Simultaneously, he had pledged a substantial sum to Rome to contribute to the rebuilding of Saint Peter’s Basilica. Pope Leo X also desperately needed funds for the basilica, which was in a state of disrepair, hoping to leave behind a magnificent new structure as his legacy. They agreed to split the profits from the indulgence sales.

Portrait of Johann Tetzel: A portrait of Johann Tetzel, the infamous indulgence seller whose activities directly provoked Martin Luther’s challenge.

Johann Tetzel, an exceptionally effective indulgence salesman, was dispatched to the region. He employed theatrical displays, often involving pyrotechnics to simulate the fires of purgatory, emphasizing what could be avoided through purchase. Tetzel is frequently attributed to the popular phrase about coins and coffers, although it likely predates him. Regardless of its origin, Tetzel certainly utilized it to great effect. Martin Luther, a professor at the University of Wittenberg, had already expressed reservations about indulgences in his earlier sermons. However, Tetzel’s proximity compelled him to engage fellow theologians and clergy in a formal debate regarding the legitimacy and morality of indulgence sales. This direct provocation by Tetzel is the immediate answer to why Martin Luther objected to indulgences and took public action.

Luther’s 95 Theses: Challenging the Foundation of Indulgences

On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther, according to tradition, posted his 95 Theses on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. He strategically chose All Saints’ Eve because the church would be open on All Saints’ Day for the veneration of relics and the sale of indulgences, maximizing public visibility. Following the posting, Luther sent a copy to Archbishop Albrecht von Brandenburg, unaware of the archbishop’s financial arrangement with the Pope. The Theses, written in Latin, were intended as propositions for academic debate, a common practice at the time, and were not initially conceived as a radical challenge to Church authority.

Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses Nailed to the Wittenberg Church’s Door: A symbolic depiction of Martin Luther posting his 95 Theses, an act that is considered the starting point of the Protestant Reformation.

Upon receiving the Theses, Albrecht von Brandenburg had them examined for heresy and then forwarded them to Rome, elevating the matter to an official Church issue. Concurrently, in early 1518, Luther’s supporters translated the Theses into German and published them, presenting what appeared to the general populace as ninety-five direct challenges to papal authority and Church policies. Luther’s core objection to indulgences is clearly articulated throughout the Theses and in his subsequent writings:

Indulgences are positively harmful to the recipient because they impede salvation by diverting charity and inducing a false sense of security. Christians should be taught that he who gives to the poor is better than he who receives a pardon. He who spends his money for indulgences instead of relieving want receives not the indulgence of the pope but the indignation of God…Indulgences are most pernicious because they induce complacency and thereby imperil salvation. Those persons are damned who think that letters of indulgence make them certain of salvation.

Initially, Luther sought only to initiate a discussion on indulgences and the true nature of penance. However, his Theses rapidly became a rallying cry for the common people against the established order. They also gained the support of Luther’s ruler, Frederick III (the Wise, 1463-1525). The Church’s attempts to silence Luther backfired, leading him to question the entire structure, ideology, and legitimacy of the Church hierarchy. Roper explains:

By attacking the understanding of penance, Luther was implicitly striking at the heart of the papal Church, and its entire financial and social edifice, which worked on a system of collective salvation that allowed people to pray for others and so reduce their time in purgatory. It financed a whole clerical proletariat of priests paid to recite anniversary Masses for the souls of the deceased. It paid for pious laywomen in poorhouses who said prayers for the souls of the dead, to ease their path through purgatory. It paid for brotherhoods that prayed for their members, said Masses, undertook processions, and financed special altars. In short, the system structured the religious and social lives of most medieval Christians. At its center was the Pope, who was the steward of the treasury of “merits” – grace that could be distributed to others. Attacking indulgences, therefore, would sooner or later lead to a questioning of papal power.

This prediction proved accurate. Events unfolded swiftly between 1518 and 1521. Luther directly challenged papal authority and was subsequently excommunicated. At the Diet of Worms in 1521, he was commanded to recant his views or face being declared a heretic and an outlaw. Luther’s defiant speech at the Diet of Worms, famously known as his “Here I Stand” speech, solidified his stance. He refused to recant. Frederick III intervened, providing Luther with secret protection at Wartburg Castle, saving him from potential execution.

The Reformation Ignited by Indulgences: Lasting Impact

Confined to Wartburg Castle, Luther continued to develop more comprehensive and forceful critiques of Church policy. Crucially, he translated the New Testament from Latin into German, defying the Church’s prohibition against vernacular translations. Luther’s emphasis on the primacy of faith and scripture directly challenged the Church’s claim to be the sole intermediary between God and humanity. Luther asserted that the Church and the Pope had become anti-Christ, obstructing true believers and maintaining their power through threats of eternal damnation in hell and purgatory. Indulgences, he argued, were a particularly effective tool in this system of control. Scholar Roland H. Bainton highlights the Church’s manipulative use of fear and hope:

The explanation lies in the tensions which medieval religion deliberately induced, playing alternately upon fear and hope. Hell was stoked, not because men lived in perpetual dread, but precisely because they did not, and in order to instill enough fear to drive them to the sacraments of the Church. If they were petrified with terror, purgatory was introduced by way of mitigation as an intermediate place where those not bad enough for hell nor good enough for heaven might make further expiation. If this alleviation inspired complacency, the temperature was advanced on purgatory, and then the pressure was again relaxed through indulgences.

The Church’s refusal to acknowledge Luther’s criticisms triggered the Reformation, initially in Germany and subsequently across Europe. Luther’s defiance inspired others, such as Huldrych Zwingli (1484-1531) in Switzerland and John Calvin (1509-1564) in France. The erosion of the Church’s absolute authority led to the emergence of reformers in various regions, each developing their interpretations of Christianity and scripture.

Protestant Reformation in Switzerland: An image illustrating the spread of the Protestant Reformation, highlighting Switzerland as one of the key regions influenced by Luther’s movement.

The Catholic Church eventually responded to Luther and the Reformation with the Counter-Reformation (1545-c. 1700). This period saw internal reforms and a reevaluation of Church policies, including a moderation and reassessment of indulgences. While indulgences are still granted by the Catholic Church today, their understanding has evolved. They are now understood as granting remission of temporal punishment for sins, not as a release from purgatory for oneself or others.

In conclusion, why did Martin Luther object to indulgences? His objection was rooted in his theological convictions, his observation of their widespread abuse and commercialization, and his belief that they undermined true repentance and salvation. Had the Church addressed these issues before 1517, the Protestant Reformation might have been averted, or at least taken a different course. However, the Church’s perceived unshakeable authority and its inability to recognize the validity of Luther’s concerns ultimately led to the fracturing of Western Christianity and the irreversible reshaping of the religious and political landscape of Europe. Luther’s challenge to indulgences was not merely a dispute over Church practice; it was a fundamental challenge to the very foundations of papal authority and medieval religious doctrine, ultimately changing the course of history.