Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are a widespread health issue, particularly affecting women. The challenge of recurring infections and the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria are making UTIs a significant public health concern. So, Why D-mannose is gaining attention? This simple sugar offers a promising approach to both prevent and treat UTIs, working in a unique way that bypasses many of the problems associated with traditional antibiotics. Let’s delve into the science and studies behind d-mannose and explore why it’s becoming a favored alternative for managing UTIs.

1. Understanding Acute Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections: The Basics

Urinary tract infections are incredibly common, impacting millions globally each year [1]. While anyone can get a UTI, women are significantly more susceptible [2,3]. UTIs are categorized based on location: lower UTIs (cystitis) in the bladder and upper UTIs (pyelonephritis) in the kidneys [2,4]. Lower UTIs are further classified as uncomplicated or complicated. Uncomplicated lower UTIs, or acute uncomplicated cystitis (AUC), typically occur in otherwise healthy women without underlying urinary tract issues [2,4].

Several factors increase the risk of cystitis in women, including a history of UTIs, sexual activity, vaginal infections, family history of UTIs, diabetes, and even genetic predisposition [2,4,5,6].

The culprits behind UTIs are usually microorganisms, with Escherichia coli (E. coli) being the most frequent offender in both uncomplicated and complicated cases [7]. Other bacteria like Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and Enterococcus faecalis, as well as fungi such as Candida species, can also cause these infections [7].

2. The Antibiotic Era and the Rise of Resistance: Why Alternatives are Needed

Antibiotics have long been the standard treatment for UTIs, and for good reason—they target bacterial infections directly. Guidelines often recommend antibiotics like fosfomycin trometamol, pivmecillinam, or nitrofurantoin as first-line treatments for uncomplicated UTIs [4,8]. While many uncomplicated UTIs can resolve on their own, antibiotics are commonly prescribed [4]. Often, this treatment is empirical, meaning it’s given without identifying the specific bacteria or its antibiotic sensitivities [9].

However, the widespread use of antibiotics comes with significant downsides. Beyond disrupting the natural balance of bacteria in the vagina and gut, antibiotic resistance is a growing threat [10,11,12]. Furthermore, recurrent UTIs are common, affecting 20–30% of women within months of an initial infection [13]. Recurrent UTI (rUTI) is defined as multiple infections within a year [2]. Repeated antibiotic use for rUTIs can lead to resistance against previously effective drugs [11,14]. The combination of high recurrence rates and increasing antibiotic resistance creates a serious public health challenge, impacting healthcare resources and quality of life [12,15,16]. This is why the search for alternative UTI treatments like d-mannose is so critical [11,17].

3. D-Mannose: A Different Approach to UTI Treatment – Unpacking “Why D”

Why is d-mannose different? It doesn’t kill bacteria like antibiotics. Instead, d-mannose works by preventing bacteria from adhering to the urinary tract walls, a crucial first step in infection. Bacterial adhesion is essential for colonization and infection; interfering with this process can be a powerful way to prevent and treat UTIs [3,18].

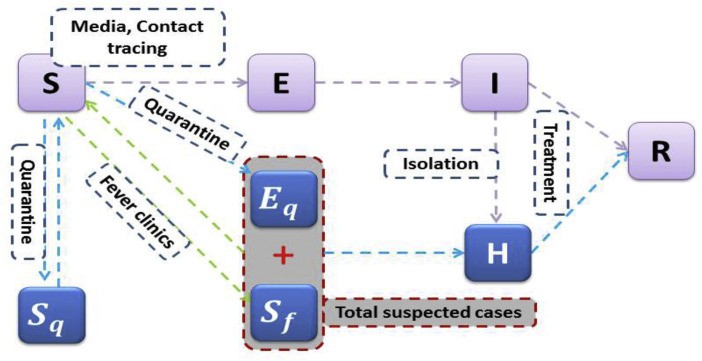

Uropathogens, especially E. coli, use finger-like projections called fimbriae or pili to attach to the bladder lining [19]. Type 1 pili of E. coli, the main UTI-causing bacteria, have a protein called FimH at their tips. This FimH protein binds to mannose sugars on the surface of bladder cells (urothelium), specifically to uroplakin 1a (Figure 1A) [20,21]. FimH is vital for E. coli to cause UTIs and is consistent across different E. coli strains [22], making it a prime target for treatment [23].

D-mannose, structurally similar to the mannose on bladder cells, acts as a decoy. When you ingest d-mannose, it’s excreted in the urine and coats the urinary tract. The FimH on E. coli preferentially binds to the free d-mannose in the urine instead of the mannose on your bladder cells (Figure 1B) [17,18]. This prevents the bacteria from sticking, allowing them to be flushed out with urine. This simple yet effective mechanism is why d-mannose is gaining traction as a UTI solution.

Figure 1.

Exogenous d-mannose in UTI: mode of action scheme. (A) Adherence of uropathogens depends on binding of the adhesin, e.g., FimH protein (located at the tips of the bacteria’s type 1 pili) to mannosylated proteins, such as uroplakin 1a, located on the epithelial cell surface. (B) Exogenously delivered d-mannose can prevent adhesion of E. coli by saturating the FimH binding sites. Thus, d-mannose competitively inhibits adhesion of bacteria to the urothelium and facilitates their clearance by urine flow. GlcNAc: N-acetylglucosamine.

4. Clinical Evidence: Does D-Mannose Really Work?

The question isn’t just why d-mannose should work, but does it work in real-world scenarios? Numerous clinical studies have explored the effectiveness of d-mannose for both treating acute UTIs and preventing recurrent ones.

One early study by Domenici et al. assessed d-mannose in treating acute uncomplicated UTIs and preventing recurrences in 43 women [18]. They found significant symptom improvement with 1.5 g of d-mannose twice daily for three days, followed by once daily for 10 days. For recurrence prevention, a group received d-mannose once daily for a week every other month for six months, while another group did not. The recurrence rate was much lower in the d-mannose group (4.5%) compared to the untreated group (33.3%). The time to UTI onset was also significantly longer in the prophylaxis group. Importantly, no side effects were reported, even with long-term use [18].

Porru et al. conducted a randomized crossover trial with 60 women experiencing acute symptomatic UTIs and recurrent UTIs [24]. Patients received either antibiotics (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) or d-mannose (3 × 1 g daily for 2 weeks), followed by prophylaxis with either antibiotics or d-mannose for 5 months. The d-mannose group had a significantly longer time to UTI recurrence (200 days) compared to the antibiotic group (52.7 days). Again, no significant side effects were noted with d-mannose [24].

Kranjčec et al. investigated d-mannose for rUTI prevention in a randomized controlled trial [25]. After initial antibiotic treatment, 308 women were divided into groups receiving daily d-mannose (2 g), nitrofurantoin, or no prophylaxis. Recurrence rates were lowest in the d-mannose group (14.6%), followed by nitrofurantoin (20.4%), and highest in the no prophylaxis group (60.8%). D-mannose was as effective as nitrofurantoin in reducing rUTI risk and had significantly fewer side effects [25].

A 2020 meta-analysis by Lenger et al. reviewed d-mannose for reducing UTI recurrence in women [27]. Compared to placebo, d-mannose significantly reduced rUTI risk. When compared to preventive antibiotics, d-mannose showed similar efficacy in preventing rUTIs [27]. These studies collectively answer why d-mannose is a viable option – it has demonstrated efficacy in both treating and preventing UTIs in clinical settings.

5. Diagnosing UTIs and Measuring Treatment Success: The ACSS

Accurate diagnosis and consistent measurement of treatment outcomes are crucial in UTI research. Acute uncomplicated cystitis is typically diagnosed based on symptoms like painful urination (dysuria) and frequent urination (pollakiuria), in the absence of vaginal issues [2,4,28]. However, definitions for diagnosis and treatment success can vary across studies.

The acute cystitis symptom score (ACSS) is a validated questionnaire that measures patient-reported outcomes for women with AUC, assessing symptoms and their impact on quality of life [29]. Validated in multiple languages, the ACSS is a reliable tool for diagnosing AUC and monitoring treatment progress [30,31,32,33,34]. It’s used in clinical studies as a “patient-reported outcomes measure” (PROM) [31,32,35,36,37,38].

The ACSS “typical symptoms” subcategory includes six items: urination frequency, urgency, dysuria, suprapubic pain, incomplete bladder emptying, and blood in urine. Symptom intensity is rated on a scale from 0 (none) to 3 (pronounced) [29]. A score of ≥6 in this domain indicates a clinical diagnosis of AUC [29,39]. The ACSS aligns with FDA and EMA guidelines for AUC diagnosis [40,41,35], making it a valuable tool for UTI research and clinical practice.

6. Re-evaluating D-Mannose Efficacy: A Post Hoc Analysis

To further understand why d-mannose is effective in acute UTIs, a post hoc analysis was conducted on data from a non-interventional study (NIS) by Wagenlehner et al. [42]. This original study assessed a d-mannose product for women with acute uncomplicated UTIs. Patients were grouped based on treatment: d-mannose alone, d-mannose with antibiotics, and d-mannose with other therapies. D-mannose dosage was 2 g three times a day for the first three days, then twice daily for days 4 and 5. Patients tracked symptoms for up to seven days. Healing was defined as symptom relief by day 7.

The original NIS found that after three days, 85.7% of the d-mannose monotherapy group were healed, compared to lower rates in the combination groups. By the final day, healing rates were similar across groups, but symptom-free rates were higher in the monotherapy group [42]. Side effects were mild and infrequent, mostly gastrointestinal issues, and potentially linked to d-mannose in a small number of cases, often in combination with antibiotics [42].

6.2. Applying ACSS to NIS Data for Deeper Insights

In the post hoc analysis, NIS symptom data was mapped to the ACSS “typical” domain. Symptoms present in the NIS were scored as “2” on the ACSS, absent as “0”. The NIS used a six-point scale for one symptom, which was converted to the ACSS four-point scale (Table 1). To balance the NIS’s five symptoms with the ACSS’s six, the “burning/pain during urination” symptom was counted twice.

Table 1.

Transfer of clinical symptoms from Wagenlehner et al. (2020) to ACSS “Typical Domain”.

| Symptom | Original Assessment | Rules for Transfer to ACSS “Typical Domain” |

|---|---|---|

| Urination frequency | 0–3 | 0–3 (no adaptation necessary) |

| Urination urgency | No, yes | No ⇒ 0; yes ⇒ 2 |

| Urination burning/pain (rated twice) | 0–5 | 0 ⇒ 0; 1 ⇒ 1; 2, 3 ⇒ 2; 4, 5 ⇒ 3 |

| Incomplete bladder emptying | No, yes | No ⇒ 0; yes ⇒ 2 |

| Visible blood in urine | No, yes | No ⇒ 0; yes ⇒ 2 |

Patients included in the post hoc analysis had physician-diagnosed AUC, follow-up exams, and an initial ACSS “typical” domain score ≥ 6. Clinical cure was defined using ACSS thresholds, specifically threshold “B” (score ≤4 and “no visible blood in urine”) and a stricter modified threshold (score ≤ 2 and “no visible blood in urine”) [36].

6.3. D-Mannose Cure Rates: Reanalyzed with ACSS

The post hoc analysis focused on d-mannose monotherapy and a combined group of d-mannose with other non-antibiotic measures. After applying inclusion criteria, 23 monotherapy patients and 36 in the combined group were analyzed.

In the d-mannose monotherapy group, the median ACSS “typical domain” score decreased rapidly from 9.0 at baseline to 2.0 by day 3, and 0.0 by day 4 (Figure 2A). The combined group showed a similar decrease from 10.0 to 3.0 by day 3, reaching 0.0 by day 7 (Figure 2B). Symptom reduction was similar in both groups.

Figure 2.

Median aligned ACSS of “typical domain” (aACSS-TD) over 7 days for patients receiving (A) d-mannose monotherapy or (B) d-mannose and other measures except antibiotics. Clinical symptoms assessed in the NIS were transferred to the “typical domain” of the ACSS. The pooled summary score of the treated cohort is shown for each day as a box plot. The red line indicates the median aACSS-TD.

Using ACSS threshold “B”, the estimated cure rate for d-mannose monotherapy was 91.3% (95% CI 72–99%; Table 2). For d-mannose with other measures, it was 86.1% (95% CI 71–95%; Table 2). With the stricter threshold, cure rates were slightly lower but still high (Table 2). Kaplan-Meier estimates showed similar symptom resolution trends in both d-mannose groups, with a slight trend towards faster resolution in the monotherapy group.

Table 2.

Time course of the summary aligned ACSS “typical” domain (aACSS-TD) and the estimated cure rates of patients receiving d-mannose monotherapy or d-mannose and other measures.

| Group 1: d-Mannose Monotherapy (n = 23) | Group 2: d-Mannose and Other Measures (n = 36) |

|---|---|

| Day | aACSS-TD (Median) |

| 0 | 9.0 |

| 1 | 9.0 |

| 2 | 4.0 |

| 3 | 2.0 |

| 4 | 0.0 |

| 5 | 0.0 |

| 6 | 0.0 |

| 7 | 0.0 |

| Cure rate [95% CI] on day 7 | – |

1 Score ≤ 4 and “no visible blood in urine”; 2 score ≤ 2 and “no visible blood in urine”.

7. Comparing Cure Rates: D-Mannose vs. Antibiotics

To put these findings in perspective, it’s important to compare d-mannose cure rates with those of standard antibiotic treatments. Meta-analyses of antibiotic treatments for cystitis show cure rates for fosfomycin around 83.8%, nitrofurantoin around 80.9%, and other antibiotics around 83.7% [44]. Placebo treatment, in contrast, shows much lower microbiological response rates of about 34.2% [45]. Clinical success rates for antibiotics like fosfomycin and nitrofurantoin are also in the 77-79% range, with other antibiotics averaging around 84.6% [46].

These figures reveal that d-mannose monotherapy, based on the post hoc analysis, achieves clinical cure rates comparable to those of commonly used antibiotics for acute uncomplicated UTIs (Figure 3). This is a key reason why d-mannose is being considered a serious alternative.

Figure 3.

Cure rates of patients with AUC treated with nitrofurantoin, fosfomycin or d-mannose [42,44,45,46]. Vertical line indicates cure rate of 75%. Squares indicate range from 1st to 3rd quartile of estimated cure rates. Horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs. 1 Random effect model. 2 d-mannose monotherapy (for numbers, see Table 2). 3 d-mannose and other measures except antibiotics (for numbers, see Table 2).

8. Symptom Relief Over Time: D-Mannose vs. Antibiotics

Beyond cure rates, the speed of symptom relief is critical for patient comfort. Comparing symptom improvement timelines between d-mannose and antibiotics is crucial to understanding why d-mannose is a patient-friendly option.

Analyzing studies that used symptom scores over time, and normalizing these scores for comparison (Table 3), reveals that symptom reduction with d-mannose is comparable to antibiotics. Normalized symptom scores at baseline were similar across treatments. By day 3, all treatments showed a significant decrease in symptom scores. After 7-8 days, symptom scores were low across all treatments.

Table 3.

Time course of mean symptom score normalized by maximum of the individual scales [%] over 1 week in AUC patients receiving d-mannose or antibiotic treatments.

| Treatment [Reference] | Baseline | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7–8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d-mannose monotherapy 1 | 51.7 | 46.9 | 28.5 | 14.5 | 5.6 | 8.3 | 11.1 | 0 |

| d-mannose and other measures 1 | 54.5 | 50.9 | 35.9 | 21.9 | 13.9 | 13.6 | 13.3 | 3.2 |

| Fosfomycin (single dose) 1 [38] | 56.1 | – | – | 25.0 | – | – | – | 11.7 |

| Fosfomycin (single dose) 2 [47] | 50.8 | 26.7 | 16.7 | 10.0 | 8.3 | 7.5 | 5.8 | 4.2 |

| Pivmecillinam (5 days) 3 [52] | 42.6 | 26.7 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 8.0 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 6.7 |

| Pivmecillinam (3 days) 1 [49] | 68.3 | 41.7 | 22.2 | 13.9 | 5.6 | 5.0 | 3.9 | – |

| Ciprofloxacin (3 days) 4 [50] | 48.3 | – | – | – | 10.8 | – | – | 5.0 |

| Ciprofloxacin (5 days) 3 [51] | 50.7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10.0 |

| Norfloxacin (3 days) 5 [48] | 46.0 | – | – | 11.6 | – | – | – | 4.0% |

| Summary of antibiotic treatment (median) | 50.7 | 26.7 | 16.7 | 12.0 | 8.2 | 7.3 | 5.8 | 5.0 |

1 6 items on scale 0–3 (max. = 18), 2 3 items on scale 0–4 (max. = 12), 3 5 items on scale 0–3 (max. = 15), 4 4 items on scale 0–3 (max. = 12), 5 5 items on scale 0–6 (max. = 30). d-mannose groups: aACSS-TD generated from NIS data; antibiotic treatments: data from controlled clinical studies [38,47,48,49,50,52] and one open clinical study [51].

Specifically, symptom scores decreased from 51.7% to 5.6% by day 4 with d-mannose monotherapy, and from 54.5% to 13.9% in the d-mannose and other measures group. The median score for antibiotic treatments decreased from 51% to 8.2% by day 4. The time-dependent symptom reduction is similar between d-mannose monotherapy and antibiotics (Figure 4), further highlighting why d-mannose is a compelling treatment option for acute UTIs.

Figure 4.

Time course of mean symptom scores in AUC over 1 week in patients receiving d-mannose compared to median symptom score in patients receiving antibiotics (for data, see Table 3).

9. Conclusion: Why Choose D-Mannose for UTIs?

This post hoc analysis, combined with existing research, strongly suggests why d-mannose is a valuable tool in managing acute uncomplicated UTIs. D-mannose monotherapy demonstrates clinical cure rates comparable to antibiotics and provides similar symptom relief within a few days of treatment. Moreover, d-mannose has shown effectiveness in preventing recurrent UTIs with minimal side effects, addressing a major concern with long-term antibiotic use.

Why should you consider d-mannose?

- Effective Cure Rates: Clinical studies and this analysis indicate d-mannose is as effective as antibiotics for acute uncomplicated UTIs.

- Reduces Recurrence: D-mannose is proven to prevent recurrent UTIs, lessening the need for repeated treatments.

- Combats Antibiotic Resistance: Its unique mechanism avoids contributing to antibiotic resistance, a growing global health threat.

- Fewer Side Effects: Studies consistently report minimal side effects with d-mannose, especially compared to antibiotics.

- Natural Approach: D-mannose offers a more natural way to manage UTIs by working with the body’s own mechanisms.

While these findings are promising and clearly answer why d-mannose is a strong contender, further randomized, controlled trials with larger patient groups are needed to solidify its role in AUC treatment guidelines. However, the current evidence makes a compelling case for d-mannose as a safe and effective alternative to antibiotics for many women experiencing acute uncomplicated UTIs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Antje Tunger (medizinwelten-services GmbH, Stuttgart, Germany) for medical writing assistance, and David Tracey (Wolfratshausen, Germany) for language and editorial support. Gesine Oberst (Stuttgart, Germany) produced the figures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.E. and P.G.; data analysis, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, O.E.; writing—review and editing, F.W., H.L. and P.G.; supervision, F.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The original non-interventional study (DRKS-ID: DRKS00016632) was funded by Cassella-med GmbH & Co. KG. Post hoc data analysis, manuscript writing assistance and APC were funded by MCM Klosterfrau Vertriebsgesellschaft mbH.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable as post hoc analysis of pre-existing data.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable as post hoc analysis of pre-existing data.

Data Availability Statement

Further data regarding post hoc analysis of the NIS are available from the sponsor by request.

Conflicts of Interest

Florian Wagenlehner reports research grants from various organizations and consultancy fees from pharmaceutical companies. Horst Lorenz has consulted for MCM Klosterfrau Vertriebsgesellschaft mbH. Oda Ewald and Peter Gerke are employees of MCM Klosterfrau Vertriebsgesellschaft mbH. MCM Klosterfrau Vertriebsgesellschaft mbH funded the post hoc analysis and manuscript writing.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral regarding jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

[1] Reference 1

[2] Reference 2

[3] Reference 3

[4] Reference 4

[5] Reference 5

[6] Reference 6

[7] Reference 7

[8] Reference 8

[9] Reference 9

[10] Reference 10

[11] Reference 11

[12] Reference 12

[13] Reference 13

[14] Reference 14

[15] Reference 15

[16] Reference 16

[17] Reference 17

[18] Reference 18

[19] Reference 19

[20] Reference 20

[21] Reference 21

[22] Reference 22

[23] Reference 23

[24] Reference 24

[25] Reference 25

[26] Reference 26

[27] Reference 27

[28] Reference 28

[29] Reference 29

[30] Reference 30

[31] Reference 31

[32] Reference 32

[33] Reference 33

[34] Reference 34

[35] Reference 35

[36] Reference 36

[37] Reference 37

[38] Reference 38

[39] Reference 39

[40] Reference 40

[41] Reference 41

[42] Reference 42

[43] Reference 43

[44] Reference 44

[45] Reference 45

[46] Reference 46

[47] Reference 47

[48] Reference 48

[49] Reference 49

[50] Reference 50

[51] Reference 51

[52] Reference 52

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Further data regarding post hoc analysis of the NIS are available from the sponsor by request.