Have you ever stopped to consider why ice cubes bob merrily on the surface of your drink, instead of sinking to the bottom? It’s a seemingly simple observation, yet it unveils fascinating principles of physics and the unique nature of water. The fact that ice floats is not just a quirky characteristic; it’s a crucial phenomenon for aquatic life and Earth’s climate. But what’s the science behind it? Let’s dive into the reasons why ice defies the norm and floats on water.

The Science of Floating: Density and Buoyancy

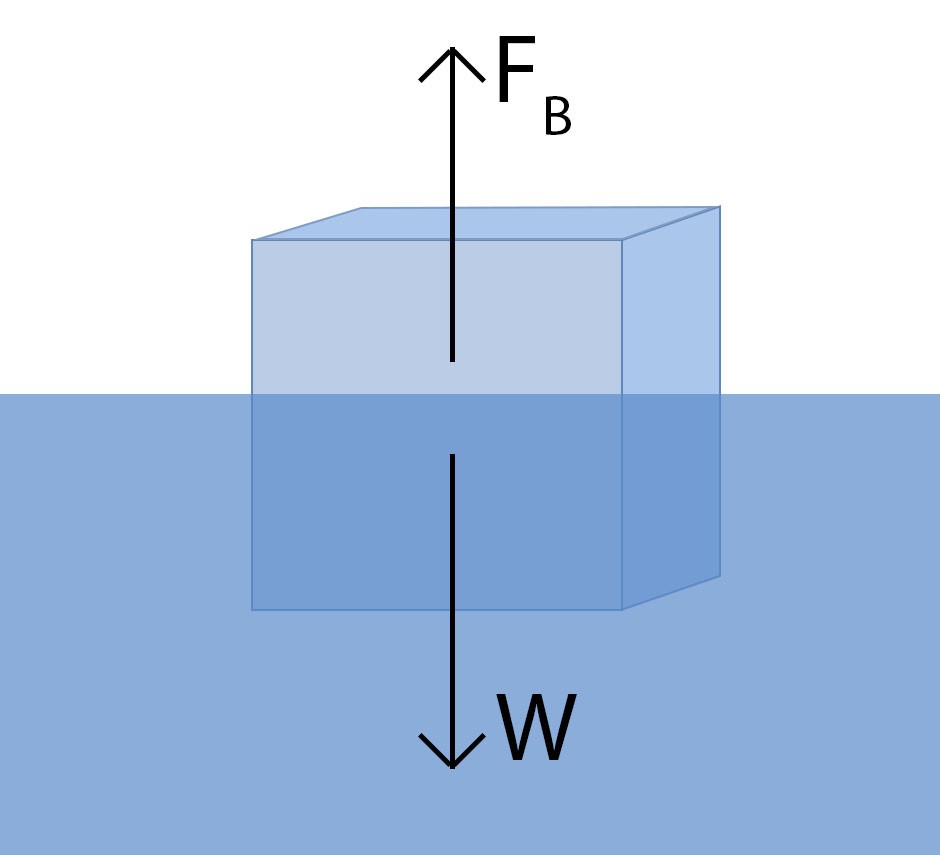

To understand why ice floats, we first need to grasp the fundamental principles of buoyancy and density. Any object, whether it’s an ice cube or a massive ship, floats because of a concept called buoyancy. Buoyancy is the upward force exerted by a fluid that opposes the weight of an immersed object. This principle is famously explained by Archimedes’ principle.

Archimedes’ principle states that the buoyant force on an object submerged in a fluid is equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the object. Imagine placing an object in water; it pushes some water out of the way, causing the water level to rise. This displaced water has weight, and that weight translates into an upward force pushing against the object.

For an object to float, this upward buoyant force must be equal to or greater than the object’s weight, which is the force of gravity pulling it down. The key factor determining whether an object floats or sinks is density. Density is defined as mass per unit volume. If an object is less dense than the fluid it’s placed in, it will float. Conversely, if it’s denser, it will sink.

Diagram illustrating the buoyant force and weight acting on an ice cube floating in water, demonstrating Archimedes’ principle.

Density and States of Matter: Why Solids Are Usually Denser

Generally, for most substances, the solid state is denser than the liquid state. This is because of how molecules arrange themselves in different states of matter. Matter can exist in different phases – solid, liquid, and gas – depending on temperature and pressure. In solids, molecules are tightly packed in a fixed, orderly arrangement called a crystal lattice.

When you heat a solid, the molecules gain energy and vibrate more vigorously. As the temperature increases, they eventually gain enough energy to break free from the rigid crystal lattice, transitioning into a liquid state. In liquids, molecules are still close together but have more freedom to move around. Heating a liquid further gives molecules even more energy to completely break free from each other, forming a gas, where molecules are widely dispersed and move randomly.

As a substance transitions from solid to liquid to gas, the molecules generally spread out, occupying a larger volume for the same mass, thus decreasing density. This is why solids are typically denser than their liquid forms.

Visualization of a crystal lattice structure, representing the ordered arrangement of molecules in solid materials.

Particle model of a liquid, showing molecules in close proximity but with freedom to move, contrasting with solid and gaseous states.

Water: An Exception to the Rule – Why Ice is Less Dense

Water, however, is an exception to this common rule. Ice, the solid form of water, is less dense than liquid water, which is why ice floats. This unusual behavior is due to a special property of water molecules called hydrogen bonding.

A water molecule (H₂O) consists of one oxygen atom and two hydrogen atoms arranged in a V-shape. The oxygen atom is more electronegative than hydrogen, meaning it attracts electrons more strongly. This unequal sharing of electrons creates a slight negative charge on the oxygen atom and slight positive charges on the hydrogen atoms, making water a polar molecule.

Illustration of a water molecule’s V-shape and polarity due to hydrogen and oxygen atom arrangement, fundamental to hydrogen bonding.

These partial charges on water molecules allow them to form weak attractions with each other, known as hydrogen bonds. In liquid water, these hydrogen bonds are constantly forming and breaking as molecules move around. However, as water cools towards freezing point (0°C or 32°F), the molecules slow down, and hydrogen bonds become more stable.

When water freezes into ice, the hydrogen bonds arrange the molecules into a specific crystal structure. In this structure, each water molecule is hydrogen-bonded to four neighbors in a tetrahedral arrangement. This arrangement creates a relatively open, hexagonal lattice structure with more space between molecules compared to liquid water. Because the molecules are further apart in ice than in liquid water, ice occupies a larger volume for the same mass, making it less dense than liquid water and causing it to float.

The Force of Freezing: Ice Expansion and Pressure

Water reaches its maximum density at about 4°C (39°F). As water cools down from 4°C to 0°C, it actually starts to expand slightly. When it freezes into ice, its volume increases by approximately 9%. This expansion exerts significant pressure.

Ice has a bulk modulus of around 8.8 x 10⁹ pascals, indicating its resistance to compression. If water is sealed in a rigid container and frozen, the pressure inside can reach enormous levels, potentially exceeding 790 megapascals (114,000 psi or 7,800 atmospheres). According to experts like Professor Martin Chaplin, no known material on Earth can withstand the pressure generated by water freezing in a completely sealed container.

High-Pressure Ice: What Happens When Ice Can’t Expand?

If water is confined in a very strong container and cooled, preventing expansion, the pressure will increase dramatically. At around 200 megapascals (2000 atmospheres), water molecules will rearrange into a denser configuration. Scientists have identified at least 13 different forms of ice, each stable at different temperatures and pressures. Ordinary ice we encounter is known as ice Ih. Under high pressure, denser forms like ice III can form. In a constrained environment, freezing water can result in a mixture of ice Ih and denser high-pressure ice forms.

In Conclusion

The seemingly simple phenomenon of ice floating on water is a consequence of water’s unique molecular properties and hydrogen bonding. This makes ice less dense than liquid water, defying the typical behavior of most substances. This unusual property of water is not just a scientific curiosity; it has profound implications for life on Earth, from insulating aquatic ecosystems in winter to influencing global climate patterns. The next time you see an ice cube floating in your drink, take a moment to appreciate the fascinating science at play!