The vibrant colors observed in the microbial world often hint at intricate biochemical processes occurring at a microscopic scale. In Streptomyces coelicolor, a bacterium renowned for its complex life cycle and antibiotic production, spore pigmentation serves as a visible marker of its developmental journey. This pigmentation, a grey hue in its wild-type form, is governed by a fascinating genetic locus known as whiE. This article delves into the whiE gene cluster, exploring its role in specifying the polyketide spore pigment and the sophisticated regulatory mechanisms that control its expression during sporulation.

Deciphering the whiE Gene Cluster: A Blueprint for Spore Pigment

Early investigations into spore pigmentation in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) revealed the presence of a grey-colored compound responsible for the characteristic spore hue. Despite challenges in purifying this pigment, its polyketide nature was predicted through the analysis of the whiE locus (14). The whiE genes bear a striking resemblance to the components of type II polyketide synthases (PKSs), enzymatic machinery crucial for the synthesis of diverse aromatic antibiotics. These include well-known examples like tetracenomycin from Streptomyces glaucescens (3), granaticin from Streptomyces violaceoruber (39), oxytetracycline from Streptomyces rimosus (26), and actinorhodin, also produced by S. coelicolor itself (16).

This prediction was substantiated when researchers successfully expressed certain whiE genes in S. coelicolor during its vegetative growth phase. This engineered expression resulted in the production of extracellular aromatic polyketides with carbon chain lengths of 22 and 24 (43), further solidifying the role of whiE in polyketide biosynthesis.

Figure 1: Organization of the whiE gene cluster in Streptomyces coelicolor. This diagram illustrates the arrangement of genes within the whiE cluster, highlighting the roles of different ORFs (Open Reading Frames) such as ketosynthase (KS), chain length factor (CLF), acyl carrier protein (ACP), aromatase (ARO), cyclase (CYC), and hydroxylase (HYDR). The cluster includes an operon of seven genes (ORFI to -VII) and a divergently transcribed gene, ORFVIII, showcasing the complexity of this genetic region.

Unveiling the Genetic Architecture of whiE: Operons and Divergent Transcription

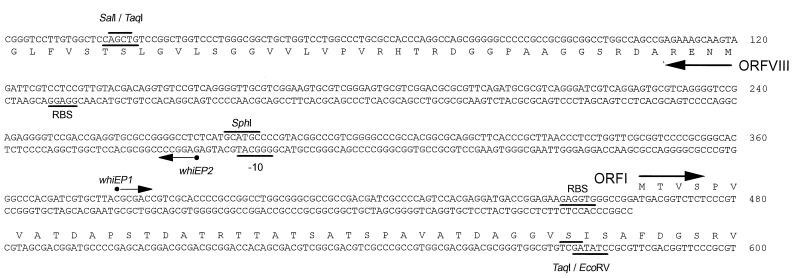

The whiE cluster, as revealed by sequencing, exhibits a sophisticated organization (Fig. 1). It comprises a likely operon of seven genes, designated ORFI to -VII, suggesting their coordinated expression. Intriguingly, it also harbors at least one divergently transcribed gene, ORFVIII, indicating a more complex regulatory landscape.

Within this cluster, specific genes are predicted to perform distinct roles in the spore pigment synthesis pathway. ORFs III to -V are believed to encode the “minimal” PKS, the core machinery responsible for assembling the primary polyketide chain. ORFs II and ORFVII are thought to encode cyclases, enzymes that catalyze ring-forming reactions, while ORFVI is predicted to encode an aromatase, crucial for introducing aromatic rings into the polyketide structure. Notably, ORFVIII stands out as encoding a putative hydroxylase, an enzyme that adds a hydroxyl group, suggesting its involvement in a late-stage tailoring step of pigment biosynthesis.

The function of ORFI remains less defined, as its product does not resemble proteins with known functions. However, it is speculated to play a role in retaining or targeting the spore pigment within the spore. Supporting this hypothesis, artificial expression of ORFs II to -VIII in the absence of ORFI resulted in the copious production of presumed pigment precursors in the surrounding medium. In contrast, when ORFI was present, the pigment remained contained within the mycelium (44). This suggests that ORFI might be crucial for the proper localization of the spore pigment. Furthermore, the possibility of additional whiE genes residing outside the currently sequenced region, encoding enzymes for further tailoring steps in the biosynthetic pathway, cannot be ruled out (44), hinting at the potential for even greater complexity within the whiE system.

Evolutionary Conservation of whiE Homologs Across Streptomycetes

Spore pigmentation is a widespread trait among Streptomyces species. Southern blot analysis, employing probes derived from different segments of the whiE cluster, has indicated that homologs of whiE are indeed prevalent throughout the streptomycete genus (5). In Streptomyces halstedii, a locus named sch has been identified, displaying remarkable similarity to whiE in both gene arrangement and sequence. The sch locus has been demonstrated to be essential for the synthesis of the spore pigment in S. halstedii, which, in contrast to S. coelicolor, is green (4–6). Similarly, a partially sequenced gene set from Streptomyces curacoi, exhibiting high similarity to whiE, is also suspected to be involved in spore pigment production, although this has not been definitively proven (1). These findings underscore the evolutionary significance of whiE-like clusters in Streptomycetes and their conserved role in spore pigmentation.

whiE as a Developmental Marker: Linking Pigmentation to Sporulation

Spore pigmentation has played a pivotal role in the genetic dissection of morphological differentiation in S. coelicolor. The original sporulation-deficient (whi) mutants were initially identified by their inability to produce wild-type levels of spore pigment. These mutants exhibited colonies that remained white even after prolonged incubation, deviating from the typical grey coloration (10, 11, 19). These observations strongly suggested that whiE expression is under developmental control, implying that understanding the regulation of whiE genes could provide valuable insights into the broader regulatory mechanisms governing sporulation. Therefore, researchers have focused on characterizing promoters within the whiE cluster and investigating their activity during development in both wild-type and sporulation-deficient strains of S. coelicolor.

Uncovering whiEP1 and whiEP2: Divergent Promoters Driving whiE Expression

To understand the regulatory landscape of whiE, researchers embarked on identifying and characterizing promoters within the whiE gene cluster. Their investigation pinpointed two divergently oriented promoters, named whiEP1 and whiEP2, residing within the 343-bp intergenic region between ORFI and ORFVIII (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Mapping Transcription Start Points of whiEP1 and whiEP2 Promoters. This image details the experimental methods used to locate the transcription initiation sites for the whiEP1 and whiEP2 promoters. (A) S1 nuclease mapping of the 5′ end of the whiEP1 transcript. (B) Primer extension analysis of the 5′ end of the whiEP1 transcript using RNA from wild-type Streptomyces coelicolor. (C) Primer extension analysis of the 5′ end of the whiEP2 transcript, also using RNA from wild-type Streptomyces coelicolor. These techniques are crucial for understanding gene regulation and promoter function.

High-resolution S1 nuclease mapping and reverse transcriptase-mediated primer extension techniques were employed to precisely map the transcription start points for these promoters. For the rightward promoter (whiEP1), mapping revealed a transcription start point at nucleotide C379, located 85 base pairs upstream of the ORFI ATG start codon (Fig. 3A and B). Similarly, for the leftward promoter, whiEP2, the transcription start point was mapped to nucleotide G272, positioned 152 nucleotides upstream of the ORFVIII ATG start codon (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3: Developmental Regulation of whiE, sigF, and hrdB Transcription. S1 nuclease protection analysis demonstrates the transcription patterns of whiE, sigF (a late sporulation-specific sigma factor gene), and hrdB (encoding the principal sigma factor) during the developmental stages of wild-type Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) in surface-grown minimal medium cultures. The time points of mycelium harvest and the presence of vegetative mycelium, aerial mycelium, and spores are indicated, providing a temporal context for gene expression during Streptomyces development.

Developmental Orchestration: whiEP1 and whiEP2 Activity During Sporulation

Having identified the whiEP1 and whiEP2 promoters, the next crucial step was to investigate their activity patterns during the developmental cycle of Streptomyces coelicolor. S1 nuclease protection assays were used to monitor the transcription dynamics of these promoters throughout development in wild-type S. coelicolor. The expression patterns of sigF, a late sporulation-specific sigma factor gene, and hrdB, encoding the essential principal sigma factor, were also examined for comparison and as controls.

Intriguingly, both whiEP1 and whiEP2 promoters exhibited developmental regulation. Their transcripts were first detected at 72 hours, a time point coinciding with the initial observation of sporulation in the culture. Transcript levels remained similar 24 hours later, suggesting a transient burst of activity during sporulation. Notably, whiE transcripts were absent during vegetative growth and aerial mycelium formation and became almost undetectable in mature 120-hour colonies (Fig. 4). This transient expression pattern strongly suggests that whiE gene expression is tightly linked to the sporulation process.

Figure 4: Dependence of whiE, sigF, and hrdB Transcription on Early whi Genes. S1 nuclease protection analysis illustrates the transcriptional activity of whiE, sigF, and hrdB in early whi mutants C119 (whiH) and C77 (whiJ) during development in surface-grown minimal medium cultures. The time points, mycelial stages (vegetative, aerial, spores), and deliberately overexposed whiE and sigF panels (to visualize weak signals) are shown, revealing the regulatory influence of early whi genes on sporulation-related gene expression.

Dependence on Early whi Genes: Placing whiE in the Regulatory Cascade

To further dissect the regulatory network governing whiE expression, researchers investigated the dependence of whiEP1 and whiEP2 promoters on other whi genes. Specifically, they examined promoter activity in representative mutants of the six early whi genes (whiA, whiB, whiG, whiH, whiI, and whiJ) known to be essential for sporulation septum formation.

Mutations in whiA, whiB, whiG, and whiI completely abolished transcription from both whiEP1 and whiEP2. In contrast, while still detectable, transcription from both promoters was significantly reduced (more than 10-fold lower than in the wild-type) in whiH and whiJ mutants (Fig. 5). As expected, the transcription of the control gene, hrdB, remained unaffected in all six whi mutants, confirming the specificity of the observed whi gene-dependent regulation.

Figure 5: Influence of sigF on whiEP1, whiEP2, and hrdB Transcription. S1 nuclease protection analysis of whiEP1, whiEP2, and hrdB transcription during development in surface-grown minimal medium cultures of the sigF null mutant J1979 and its sigF+ parent strain J1508. The time points, mycelial stages (vegetative and aerial mycelium, spores), and identical exposure times for panels are detailed, illustrating the specific requirement of sigF for whiEP2 but not whiEP1 transcription.

Dissecting Sigma Factor Specificity: whiEP2 Dependence on ςF

The late sporulation-specific RNA polymerase sigma factor, ςF, encoded by sigF, is known to play a crucial role in orchestrating late sporulation events. To investigate the potential involvement of ςF in whiE regulation, transcription of whiE was examined in a sigF null mutant strain (J1979) and its congenic sigF+ parent (J1508).

In the sigF+ strain J1508, the expression pattern of whiEP1 and whiEP2 mirrored that observed in wild-type S. coelicolor, with transcripts appearing during sporulation (Fig. 6). However, striking differences emerged in the sigF mutant. While disruption of sigF had no discernible impact on transcription from whiEP1, transcription from whiEP2 was completely abolished in the sigF mutant (Fig. 6). These findings revealed a clear distinction in the regulatory requirements of the two whiE promoters, with whiEP2, but not whiEP1, being dependent on the late sporulation-specific sigma factor, ςF.

Unraveling the Phenotype: Greenish Spores in sigF Mutants

Previous studies had shown that disruption of whiE ORFVIII results in a change in spore color from grey to greenish (44). Given the observed sigF-dependence of whiEP2, which drives transcription of whiE ORFVIII, researchers predicted that sigF mutants might also exhibit a greenish spore phenotype.

While the original sigF null mutant, J1979, was reported to have white spores (33), this observation seemed inconsistent with the predicted role of ςF in whiE ORFVIII expression. To resolve this discrepancy, a new sigF null mutant (J1984) was constructed in a different genetic background (M145). Intriguingly, the spores of J1984 were indeed greenish, demonstrating that disruption of sigF does alter the nature of the spore pigment, rather than completely preventing its synthesis. This finding was further corroborated by the observation that disruption of sigF in Streptomyces aureofaciens also leads to a change in spore pigment color, from grey-pink to green (34a).

The discrepancy in spore color phenotype between J1979 (white) and J1984 (greenish) sigF mutants might be attributed to differences in overall pigment synthesis levels in different genetic backgrounds. The greenish spore color in J1984 is quite pale, suggesting that a reduction in overall pigment production in J1979, combined with the color shift, might render the pigment undetectable, resulting in the observed white phenotype.

In Vitro Transcription Studies: Probing ςF Promoter Specificity

To determine if whiEP2 is a direct target for ςF-containing holoenzyme (EςF), in vitro transcription assays were performed using purified ςF. Despite successful purification and confirmation of the N-terminal sequence of ςF, EςF was not sufficient to direct transcription of whiEP2 in vitro (Fig. 7).

Figure 6: In Vitro Promoter Specificity of ςF-containing Holoenzyme. Runoff transcription assays evaluating the promoter specificity of ςF-containing holoenzyme in vitro. Transcription from the whiEP2 promoter region and the Bacillus subtilis ctc promoter (a known ςB-dependent promoter, used as a positive control due to similarity between ςF and ςB) are compared. The expected transcript sizes and size standards are indicated to assess the activity and specificity of ςF in directing transcription.

As a positive control for ςF activity, the Bacillus subtilis ctc promoter, known to be dependent on ςB (a sigma factor with similarity to ςF), was tested. EςF was indeed able to recognize and direct transcription from the B. subtilis ctc promoter in vitro (Fig. 7), confirming the activity of the purified ςF preparation.

The inability of EςF to directly transcribe whiEP2 in vitro, despite its sigF-dependence in vivo, suggests that the regulation of whiEP2 might be more complex than direct activation by EςF alone. One possibility is that whiEP2 transcription requires a transcription activator protein in addition to EςF. Alternatively, the in vitro conditions might not fully recapitulate the cellular environment necessary for EςF-dependent transcription of whiEP2.

Expanding the Regulatory Map of Sporulation: whiEP1 and whiEP2 in the Hierarchy

The identification and characterization of whiEP1 and whiEP2 promoters have expanded our understanding of the genetic circuitry governing sporulation in Streptomyces coelicolor. These promoters, with their distinct regulatory requirements, can now be integrated into the existing hierarchy of genes controlling sporulation in aerial hyphae (Fig. 8).

Figure 7: Dependence Hierarchy of Genes Controlling Sporulation in Streptomyces coelicolor. A model illustrating the regulatory hierarchy of genes involved in sporulation in the aerial hyphae of Streptomyces coelicolor, adapted to incorporate the newly characterized whiEP1 and whiEP2 promoters. The diagram highlights the dependence of sigF expression on early whi genes and the distinct regulatory pathways for whiEP1 and whiEP2, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of sporulation control.

The established dependence of sigF expression on the six early whi genes (25) provides a plausible explanation for the observed dependence of whiEP2 on these same early whi genes. However, the whiEP1 promoter presents a different scenario. Its dependence on early whi genes, despite being sigF-independent, suggests a distinct regulatory pathway. Furthermore, whiEP1 does not conform to the consensus sequence for promoters recognized by ςWhiG, the early sporulation-specific sigma factor (41, 42), indicating that neither ςWhiG nor ςF directly transcribes whiEP1. This implies the involvement of yet another regulatory factor in controlling whiEP1 expression.

Spatial Segregation of PKS Clusters: Cell-Type Specificity of whiE

Previous research has hinted at the possibility that whiE expression is spatially restricted to specific cell types within the developing Streptomyces colony. Streptomyces coelicolor produces not only the whiE pigment but also another polyketide compound, the blue antibiotic actinorhodin, encoded by the act cluster (16). Interestingly, mutations in the minimal PKS subunit genes of either act or whiE are not complemented in trans by the corresponding genes from the other cluster under normal conditions. However, functional hybrid PKS complexes can be formed when whiE PKS genes are artificially expressed in act mutants, or vice versa, under the control of an inducible promoter (27, 44).

These findings suggest that the lack of “cross-talk” between the act and whiE PKS systems under normal circumstances is not due to biochemical incompatibility but rather to their expression in distinct cell types within the developing colony. The temporal regulation of whiEP1 and whiEP2 activity, specifically during sporulation in aerial mycelium, and their dependence on early whi genes, further strengthens the hypothesis that whiE expression is confined to the spore compartments. This cell-type specific expression ensures the precise spatial and temporal coordination of secondary metabolite production during the complex developmental program of Streptomyces.

Greenish Mutants and the Hydroxylase Tailoring Step

whiE ORFVIII is predicted to encode a hydroxylase, likely responsible for a late-stage tailoring step in the spore pigment biosynthetic pathway, specifically the introduction of a hydroxyl group into the cyclized polyketide. The homology of ORFVIII to flavin adenine dinucleotide-linked hydroxylases (6) and the greenish spore phenotype observed upon its disruption (44) strongly support this role. Similarly, disruption of the ORFVIII homolog in the sch cluster of S. halstedii also results in a spore color change (6), further emphasizing the conserved function of this hydroxylase in spore pigment modification.

Intriguingly, early screens for whi mutants of S. coelicolor identified six mutants with greenish spores (18). Five of these mutants mapped to a chromosomal location consistent with the whiE locus (18), suggesting that they might harbor mutations in whiE ORFVIII. The remaining greenish mutant, C27, mapped to a location compatible with sigF (18, 34), raising the possibility that C27 might be a sigF mutant, a hypothesis now supported by the greenish phenotype of the constructed sigF null mutant J1984.

Concluding Remarks: whiE and the Intricate Control of Streptomyces Development

In conclusion, the whiE gene cluster and its divergently oriented promoters, whiEP1 and whiEP2, represent a fascinating example of the intricate regulatory mechanisms governing secondary metabolite biosynthesis during bacterial development. The developmental and genetic dissection of whiE expression has provided valuable insights into the sporulation process in Streptomyces coelicolor, revealing a complex interplay of sigma factors, regulatory genes, and cell-type specific expression. Further research into the precise regulatory factors controlling whiEP1 and the potential transcription activators involved in whiEP2 regulation will undoubtedly continue to refine our understanding of this captivating developmental system.

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to Mark Paget, Mervyn Bibb, and David Hopwood for their insightful comments and feedback on the manuscript.

This work was supported by BBSRC grant CAD 04355 (to M.J.B.), by a Lister Institute research fellowship (to M.J.B.), and by a grant-in-aid to the John Innes Centre from the BBSRC.