Scientists have been pondering a fascinating question for decades: are viruses alive? This question isn’t just academic; understanding the nature of viruses is crucial for developing effective treatments and preventing pandemics. While viruses can replicate and evolve, much like living organisms, they lack several key characteristics that define life as we know it. This article delves into the intriguing reasons behind why viruses are typically classified as non-living entities, exploring the unique biology that places them in this gray area.

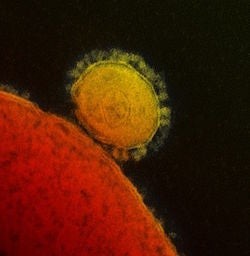

Alt text: Illustration depicting a virus particle attaching to a host cell, highlighting the interaction necessary for viral replication.

What Defines Life? The Criteria for Living Organisms

To understand why viruses are excluded from the realm of life, we first need to define what constitutes a living organism. Biologists generally agree on a set of fundamental characteristics that define life. These include:

- Cellular Structure: Living things are composed of one or more cells, the basic units of life.

- Reproduction: Living organisms can reproduce, creating offspring either sexually or asexually.

- Metabolism: Living beings carry out metabolic processes, using energy to grow, maintain themselves, and function.

- Homeostasis: Living things maintain a stable internal environment, despite external changes.

- Response to Stimuli: Living organisms react to changes in their environment.

- Growth and Development: Living things grow and develop throughout their life cycle.

- Evolutionary Adaptation: Living populations can evolve and adapt to their environment over generations.

Viruses and the Characteristics of Life: Where Do They Fall Short?

When we examine viruses against these criteria, some significant discrepancies emerge, leading to their classification as non-living.

Lack of Cellular Structure

One of the most fundamental reasons viruses are not considered alive is their acellular nature. Unlike bacteria, plants, or animals, viruses are not made up of cells. Instead, they have a remarkably simple structure. A typical virus consists of genetic material, either DNA or RNA, enclosed within a protective protein coat called a capsid. Some viruses may also have an outer lipid envelope derived from the host cell membrane. They lack essential cellular components like a cell membrane, cytoplasm, and organelles such as ribosomes or mitochondria, which are vital for cellular functions.

Dependence on Host Cells for Reproduction

While viruses possess genetic material and can “reproduce,” their reproductive strategy is entirely dependent on hijacking living cells. Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites, meaning they can only replicate inside a host cell. They lack the necessary machinery, such as ribosomes and enzymes, to independently synthesize proteins and replicate their genetic material. Instead, viruses commandeer the host cell’s cellular machinery to produce viral components and assemble new viral particles.

Alt text: Cartoon illustration of a virus particle, emphasizing its inactive state outside of a host cell and its activation upon encountering one.

Even though some recently discovered giant viruses, like mimiviruses, possess a more complex genetic makeup and some genes related to DNA replication and protein synthesis, they are still reliant on host cells for complete replication. The discovery of mimiviruses has blurred the lines slightly, prompting ongoing discussions about the definition of life and the classification of these complex viruses.

Absence of Independent Metabolism and Energy Use

Outside of a host cell, viruses are inert and metabolically inactive. They do not carry out any metabolic processes on their own, nor do they utilize energy independently. Viruses only become “active” when they invade a host cell. Once inside, they exploit the host cell’s metabolic resources and energy to synthesize viral components and drive their replication cycle. This complete reliance on the host cell for energy and metabolic functions further distinguishes viruses from living organisms that possess their own metabolic systems.

Limited Response to the Environment

The ability of viruses to respond to their environment is a subject of debate. Viruses can interact with host cells, binding to specific receptors on the cell surface, and their genetic material can undergo mutations and evolve over time, particularly within an infected organism. However, these interactions are largely determined by their structural and chemical properties rather than active responses to environmental stimuli in the way living organisms do. Processes like binding to receptors are driven by chemical interactions, and evolution occurs through random mutations acted upon by natural selection, not through conscious adaptation.

The Ongoing Debate and the “Gray Area” of Life

The classification of viruses remains a subject of ongoing discussion and highlights the challenges in definitively defining life. Viruses occupy a fascinating gray area between the living and non-living. They possess genetic material and can evolve, characteristics associated with life, but they lack cellular structure, independent metabolism, and self-replication capabilities, traits considered essential for living organisms.

Ultimately, whether viruses are considered “alive” may come down to philosophical perspectives and the precise definition of life. From a practical standpoint, understanding their non-living nature is crucial for developing strategies to combat viral infections.

If Viruses Are Not Alive, How Can We “Deactivate” Them?

Regardless of their classification, we know that viruses can be rendered inactive, preventing them from infecting host cells. This “deactivation” is often mistakenly referred to as “killing” viruses, but since they aren’t considered alive, the term is technically inaccurate.

Viruses can be deactivated through various means, depending on their structure. Viruses with a lipid envelope, like the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19, are susceptible to soap and detergents. Soap molecules disrupt the lipid envelope, causing the virus to fall apart and become non-infectious. This is why thorough handwashing with soap and water is so effective in preventing the spread of enveloped viruses.

Viruses with a protein capsid, lacking a lipid envelope, are not deactivated by soap in the same way. However, soap and water can still physically remove these viruses from surfaces, washing them away and reducing the risk of transmission. Hand sanitizers, while effective in killing bacteria and some viruses, may not be as effective as soap and water in physically removing viruses from the skin.

Understanding the structural differences in viruses informs our strategies for preventing their spread and developing antiviral treatments. Whether living or non-living, viruses have a profound impact on life on Earth, driving ongoing research and debate about their fundamental nature.