One morning, the unsettling rattle Josy heard when she turned on her 2010 Prius was a sound her girlfriend, Glory, knew all too well. Thieves had struck again at Glory’s Indianapolis apartment complex, targeting catalytic converters – the unassuming car part vital for reducing harmful emissions. For Glory, a 23-year-old librarian, this was a grim repeat; her 2016 Kia Sportage had already been victimized twice. Now, it was Josy’s turn.

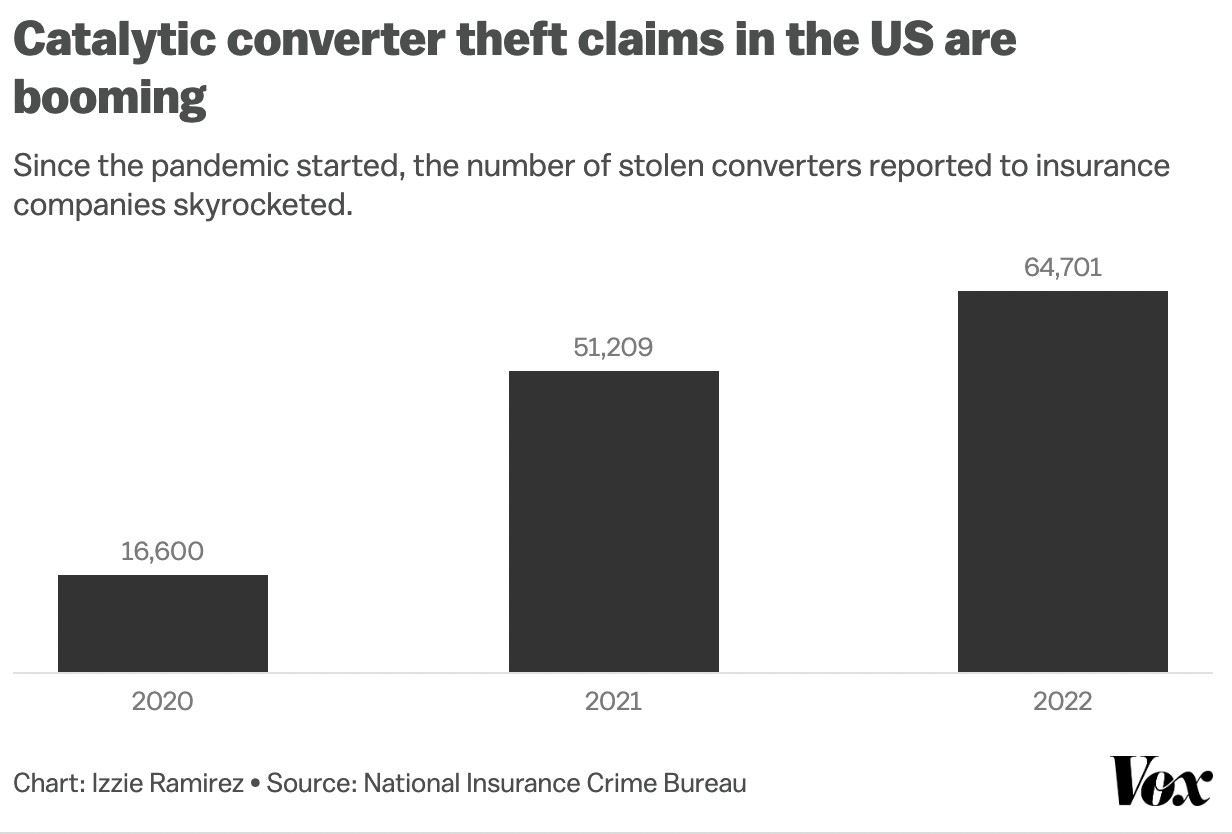

Josy and Glory, whose last names remain private for security, are far from isolated cases. Across the United States, from San Diego to Boston, catalytic converter thefts have reached alarming levels. Data from the National Insurance Crime Bureau reveals a staggering increase in insurance claims, jumping from 16,660 in 2020 to 64,701 in 2022.

Catalytic converters might seem like an odd target, but their value lies in the precious metals they contain: platinum, palladium, and rhodium. A stolen converter can net a thief a quick profit of a few hundred dollars. In the US, these used converters are not repurposed for vehicles but are instead sent to refineries to extract these valuable metals.

These thefts are often audacious, happening in broad daylight and completed in under 90 seconds. The untraceable nature of detached catalytic converters has historically hampered police efforts. Tragically, confrontations during thefts have sometimes escalated to violence.

Replacing a stolen catalytic converter can be costly, potentially reaching thousands of dollars, and time-consuming, often involving weeks of waiting. Like other car parts, converters are vehicle-specific. While most cars have one, some have two, and others up to four. Owners of electric vehicles are spared this worry, as only combustion engine and hybrid cars are equipped with these devices.

While these thefts might seem like random, isolated incidents, the reality is a large-scale, organized criminal activity. A recent Department of Justice crackdown exposed a $545 million nationwide theft ring, resulting in 21 arrests and the seizure of millions in assets.

Unfortunately, 2023 appears to be continuing this troubling trend. While drivers can take preventative measures, the escalating problem necessitates action from lawmakers and car manufacturers.

What is a Catalytic Converter?

The technology within a catalytic converter is remarkably sophisticated. Essentially, this component, roughly the size of a loaf of bread and located beneath your car, converts harmful engine exhaust gases into less environmentally damaging substances. Internally, it features a honeycomb-like structure composed of platinum, palladium, rhodium, and other metals, which facilitate the chemical conversion process.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

To understand its function, consider the engine. Whether it’s a 4-cylinder or 8-cylinder engine, each start initiates numerous small combustions in each cylinder, powering your vehicle. According to Talena Handley, a California-based mechanic and owner of Girlie Garage, these combustions generate fumes that must be expelled. The catalytic converter steps in to transform these fumes into nitrogen, carbon dioxide, water, and oxygen, which are then expelled through the muffler and tailpipe.

Before catalytic converters, vehicles released untreated exhaust directly into the atmosphere. It was the Clean Air Act of 1970%20sources%20and%20mobile%20sources.) by the EPA that mandated vehicle emission regulation in the US. By 1975, catalytic converters became a standard requirement for most cars to meet these new emission standards. An interesting side effect of this legislation was the push for companies to eliminate lead from gasoline as it damages converters. By 1986, leaded gasoline was completely phased out in the US.

The Surge in Catalytic Converter Theft: Pandemic and Precious Metals

A key question surrounding the dramatic increase in catalytic converter theft is: “Why the sudden spike?” The answer is linked to pandemic-driven disruptions in the supply chain, particularly for precious metals.

Platinum, palladium, and rhodium are mined metals with limited availability. Rhodium, the rarest and most valuable, is primarily sourced from South Africa and Russia.

While thefts were gradually increasing since 2019, the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 saw an explosion in these crimes, according to experts. Pandemic restrictions hampered mining, processing, and shipping of these metals globally, leading to supply chain bottlenecks.

Compounding this, fewer people were driving their cars at the pandemic’s onset, creating a surplus of parked, vulnerable vehicles. Simultaneously, the value of these precious metals soared, creating a powerful incentive for catalytic converter theft.

Donovan Bates, owner of DMV Recycling, a Virginia-based metal recycling firm, explains, “There’s other people who are illegally enjoying the ride saying, ‘Okay, if these precious metals are up high, we’re going to go and take them.'” His company purchases converters from individuals and mechanics, later selling them to refineries, while ensuring proper tracking of sources.

The price of catalytic converters varies based on vehicle year, make, and model. Hybrid vehicles, such as the Toyota Prius, are prime targets due to their higher concentration of precious metals. The Los Angeles Times reports that the Prius is the most targeted car in the Western US (and California is the leading state for thefts, according to NICB). With two catalytic converters valued at up to $1,000 each, they offer a significant payout for thieves.

Other frequently targeted vehicles include fleet vehicles (like USPS trucks, school buses, and even Oscar Mayer’s Wienermobile) which are often parked in unsecured lots, and vehicles with higher ground clearance such as trucks and SUVs. These vehicles provide easier access for thieves to slide underneath and remove the converter undetected.

However, thefts are not always without risk for the perpetrators. In February, a thief attempting to steal a converter from a Ford Excursion in California was fatally injured when the vehicle’s sleeping driver awoke and inadvertently ran over the thief.

Handley and Bates note that thieves typically work in teams, enabling them to target multiple vehicles quickly in a single location. Equipped with electric saws or similar tools, they can remove a converter in minutes.

A concerning aspect is the increased vulnerability to repeat theft after replacement. Handley explains, “Because then they know that you’re vulnerable and they know you’re going to fix it…if your car is still sitting in your driveway a month later with a new catalytic converter, that new catalytic converter actually has more fresh material in it. They’re going to hit you again.”

The profitability for thieves escalates with volume. Individual converters contain only small amounts of precious metals, making bulk theft essential. In the US, many thieves sell to metal recyclers or scrap yards with lax identification checks.

These intermediaries, according to Bates, pay upfront for converters and accumulate them until they have enough volume (around 800 converters, or 2,000 pounds of material) to sell to refineries for processing. Refineries then crush the converters, refine the dust, separate the precious metals, and sell them for reuse in new converters, dental fillings, jewelry, and other applications. (Bates’ company, notably, implements stricter tracking measures, requiring driver’s licenses and business licenses).

Protecting Your Vehicle from Catalytic Converter Theft

Beyond standard safety advice like parking in garages or well-lit areas, several proactive measures can offer additional protection against catalytic converter theft.

Firstly, contacting your insurance provider to review and potentially upgrade your coverage is advisable. Victims’ experiences vary widely based on their insurance policies, with some facing significant out-of-pocket replacement costs. For those with frequently targeted vehicles, limited garage parking, or residence in high-theft areas, enhanced coverage can be a worthwhile investment.

Lyssa, a 39-year-old teacher in Oakland, upgraded her insurance after her 2005 Toyota Highlander was targeted three times in 2022, following her husband’s 2012 Prius being hit in 2020. Initially, they opted for an insurance buyout for the Prius to avoid the $1,000 co-pay. However, after repeated Highlander thefts, they upgraded their insurance and installed an anti-theft cable on the converter.

Lyssa cautions against skimping on insurance: “It can be a really painful realization if you get the cheap insurance, like one of my coworkers did, and then lose your catalytic converter and then find out that you don’t have any coverage for that. So you actually have to pay for the whole $3,000. Which, you know, if you’re driving an old Camry, that’s more than your car is worth.”

For physical deterrence, Handley recommends consulting a mechanic about installing a “cat shield,” a protective metal plate covering the converter. These range in price from $50 to $500, depending on the vehicle. Alternatives include anti-theft cables, which are more affordable but potentially easier to breach.

“The reason the cat shield actually deters people is because it takes a really long time and it’s very noisy,” Handley explains. “It takes a longer time to cut through it, so if you have to linger to cut through it, you have a higher chance of attracting attention. If they’re really determined, they’ll still do it, though.”

Etching your Vehicle Identification Number (VIN) onto your catalytic converter is another recommended step, according to recycler Bates. While converters don’t come pre-etched, recyclers encountering marked converters may be less inclined to purchase them. VIN stickers and databases for tracking are emerging, but their widespread adoption among recyclers is still limited, Bates notes.

“The real problem is that we don’t have a good infrastructure in place to stop catalytic converter theft,” Bates emphasizes.

He advocates for a state or federal database of catalytic converters, easily accessible to recyclers and repair shops, to track ownership and deter illegal sales. Manufacturer-engraved VINs on converters would streamline this process and reduce the burden on car owners. A searchable database enabling legal ownership transfer could significantly curb thefts.

Houston Police Department Sergeant Bob Carson confirms the identification challenge for law enforcement. “If I stopped you with five catalytic converters in your car,” he states, “I couldn’t connect you to any specific vehicle.” While forensic analysis can sometimes link a converter to a vehicle, it is infrequent.

Legislative and Law Enforcement Responses

The catalytic converter theft epidemic has spurred action at state and local levels. Over the past two years, numerous cities and states have proposed and enacted new laws or amended existing ones to combat this crime, according to the National Insurance Crime Bureau.

Houston’s city council, for example, passed an ordinance in 2022 requiring metal recyclers to demand stricter identification from sellers, including business or driver’s licenses and vehicle VINs. Sergeant Carson notes that this law was accompanied by community education to support the secondary market’s compliance.

Preliminary data from the Houston Police Department suggests these measures are having a positive effect. After a surge from 1,793 thefts in 2020 to 7,822 in 2021 and 9,637 in 2022, projected thefts for 2023 are around 4,000. January and February of 2023 saw fewer than 700 combined thefts. The Texas State Legislature is also considering making catalytic converter theft a felony to further deter the crime.

If your catalytic converter is stolen, promptly reporting it to your local police and insurance company is crucial. These reports provide valuable data for law enforcement and policymakers, and insurance may cover replacement costs.

Deciding whether to replace the converter or the entire vehicle depends on individual circumstances. Older vehicles might face longer wait times for parts, and repair costs could exceed the car’s value. States with less stringent emissions regulations might offer quicker access to aftermarket converters. Mechanic Handley advises getting quotes from at least three shops for price comparison and recommends immediate cat shield installation after replacement.

“There is absolutely no regulation on automotive pricing,” Handley points out. “At all. There can be two shops in the same parking lot and they will charge you different prices for the same thing.”

In the interim, vigilance remains key. Whether legislative efforts and increased awareness will reverse the national trend remains to be seen.

See More: